Yeats’ famous rhetorical question at the end of his poem, ‘Among School Children’ suggests that the dancer and the dance are fused into one, as an actor should be in his role, as a musician might be in the music she plays or sings. The power of that symbiosis is always striking when it occurs, making the audience also lose a part of themselves in what is transpiring before their eyes and ears. Such, we are told, was the effect of seeing Vaslav Nijinsky dance. Here was a being who seemed to live to dance, for whom performing was the only life. The fact that the great, innovative, legendary dancer and choreographer succumbed to schizophrenia, a condition that ended his career, means that he has become not only a figure for greatness in performance, but also for madness in the arts.

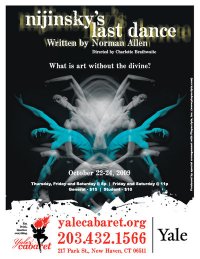

Norman Allen’s play, Nijinsky’s Last Dance, which is ending its three night run tonight at the Yale Cabaret (shows at 8 and 11 p.m.), seizes on both aspects of Nijinsky -- the inspired genius, the struggling schizophrenic -- to present a monologue in which the dancer regales the audience with his view of his life and accomplishments.

It is a life that is now all in the past, except to the extent that every moment is still intensely alive in the character’s telling: his loss of his father in childhood; his meeting with and affair with the infamous impresario Sergei Pavlovitch Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes; modelling nude for Rodin; the scandalous shows -- Le Sacre du printemps and L’après midi d’un faune; his marriage, the birth of his daughter; his sojourn in popular music hall entertainment in London; his tour of America; his final dance at the St. Moritz in Switzerland during World War I.

It’s a role that requires amazing physical stamina, notable comic and dramatic gifts, a dancer’s body, and a grab-you-by-the-lapels urgency. Danny Binstock, in the Yale Cab production, has all that. His Nijinsky is simply rivetting from first to last. Taking us into his confidence from within his cell in an asylum, Binstock delivers Nijinsky’s lines with a feverish sense of need -- he must try to make his world intelligible because -- as he shouts, sighs, pleads, again and again -- ‘I am Nijinsky!’

Few sights can offer more gripping pathos than a major innovator, past his glory, having to insist upon his triumphs -- which only exist, now, as memories in the minds of those who saw them or participated in them.

And so we are presented with the mind of Nijinsky, the only place we can turn to try to grasp what this extraordinary life was like. We hear at times the voices of people from Nijinsky’s life, to which Nijinsky reacts in various ways, sometimes mouthing their lines, sometimes seeming to argue back in distracted muttering, sometimes taking refuge in movement. Director Charlotte Braithwaite departs from the script in these voice-overs, since they are written to be spoken by the actor playing Nijinsky, but the innovation works well. Rather than watching Nijinksy become Diaghilev or his own wife, sister, or mother, we see instead the effect these voices in his head has upon the dancer.

Further, the play calls for quite a bit of physical movement. Not abounding in space, the Yale Cab is a risky place to put on such a show -- if the actor goes a little off his mark, he could find himself in a spectator’s lap or amid the remnants of someone’s dinner. So one can only marvel at how precisely Binstock uses the space available to him, while suggesting a whirlwind of movement. Brathwaite, Binstock, and producer/choreographer Jennifer Harrison Newman very inventively mime the ballet routines that were part of Nijinsky’s repertoire.

When at one point Binstock sits upon a chair to eye his audience in a pause prolonged to become uncomfortable, we see how the director has adapted the play to its space with great bravura. That moment, and the final segment in which Nijinsky upbraids the audience for allowing the war to happen, brings the play suddenly from the past, c. World War I, and the mind of a long-dead dancer, into our time-frame, where the voice of a genius -- who hears God say ‘enough!’ at the end of his last dance -- speaks to us fully in the moment.

The most intense and spirited production at Yale Cab so far this season.