Preview of Middletown, New Haven Theater Company

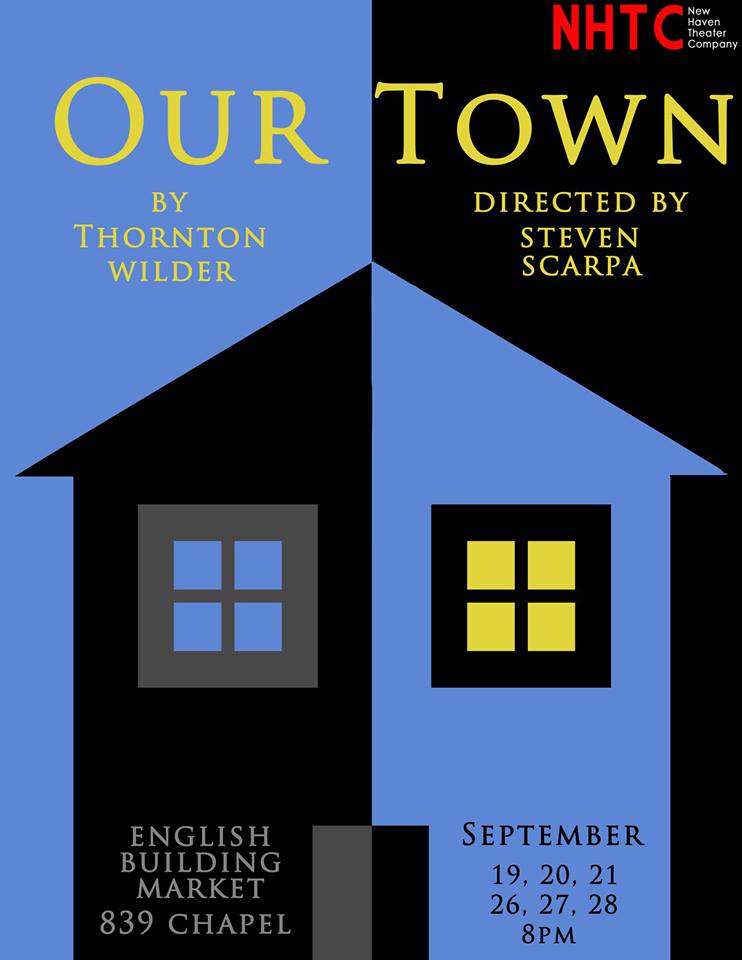

New Haven Theater Company tends to thrive on dialogue-driven plays with small casts, but, once a year or so, they go for something bigger and busier. Coming up for two weekends—the last weekend of April, the first weekend of May—is just such a project, third in the unofficial “town trilogy” that the NHTC probably weren’t even thinking about: Urinetown (in 2012), Our Town (in 2013), and now, Middletown.

Written by Will Eno, one of the most consistently interesting and entertaining writers in theater today, Middletown, which was first produced in New York in 2010, has been called a “modern Our Town,” which is to say that its setting—a kind of “Anytown, USA”—recalls Thornton Wilder’s evocation of the perennial attractions of Grover’s Corner, while its view of what makes America tick is infused by a self-conscious irony toward the normative. Then again, in the Our Town at Long Wharf a few years back, the town onstage extended to the audience and vice versa; in Eno’s Middletown, an “audience” is present onstage between acts to let us know we’re right in the middle of the world it portrays. A world that includes an astronaut in outer space and a local n’er-do-well having to serve time portraying a Native American. Both Wilder and Eno have a sense of America as a place older than the United States and with an ethos always somewhat futuristic.

What attracts the Company to “townie” plays we can only surmise, but I suspect it has something to do with the fact that NHTC is specific to our town—New Haven—and has a feel for plays with a strong sense of regular folks in a place. This time Peter Chenot directs; he starred in Urinetown, and had a part in Our Town, directed by Steve Scarpa. Now he turns the tables and directs Scarpa, as John, the lead male character, in Middletown. Chenot was also at the helm of one of the non-town-based big productions the troupe has staged: Donald Margulies’ Shipwrecked! in 2014, which was very fluid in its execution of space.

In reading the play for consideration—it was Steve Scarpa who originally proposed Middletown to the Company—Chenot said he saw it as “a challenge, for sure,” as the play calls for various locations and will require reusing the pieces of the set in different configurations. There are “scenes inside houses, outside houses, at a monument, in separate rooms in a hospital and on its loading dock, and in outer space.” It will take some ingenuity to render “so many places in the NHTC’s shallow space, but the challenge is part of the fun.”

From the start, Chenot was attracted by the fact that the play calls for much of the cast to play more than one part, and the play’s deliberate evocation of Our Town struck a chord as well. “We all know that play,” he said, and, like Wilder’s best-known work, Middletown’s “main selling point is that it left me moved and uplifted though I don’t get it yet. There’s always more to know about the best plays where you don’t grasp all the subtleties at once.” Chenot likened working on the play to doing a jigsaw puzzle, getting more of the picture the more pieces fit.

Chenot called the play “human, quirky, and intriguing.” The people in the play are “normal, and speak in a matter-of-fact way that is not lofty” but conveys “what it means to be alive right now. It’s so smart and tackles big mysteries” about the human condition. The play also keeps the audience aware of the provisional aspect of theater as there are deliberate “moments of glitch in the play,” something of an Eno trademark.

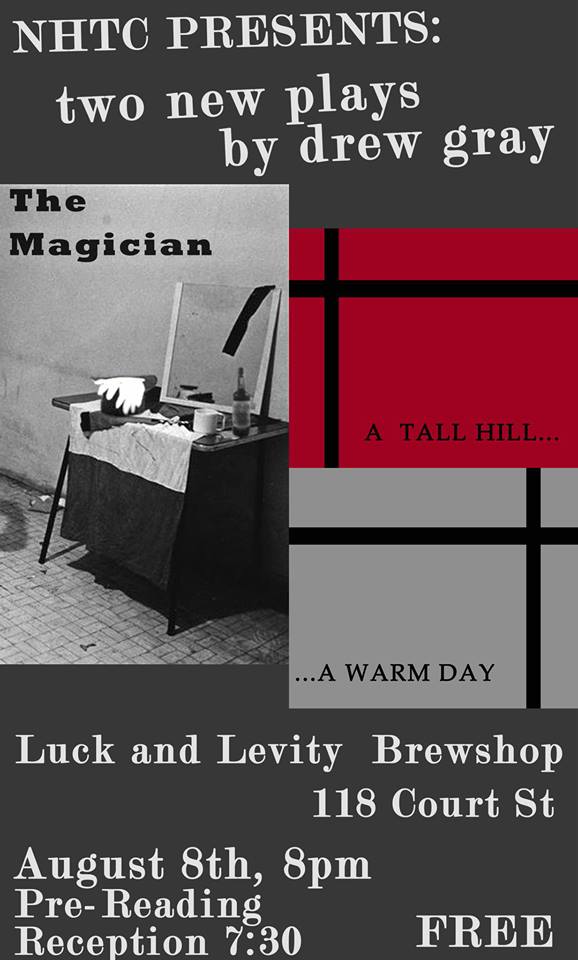

Middletown comes along now because, while the company has been considering it for almost two years, the schedules of the NHTCers aligned sufficiently to make it possible. Only three current NHTCers are not appearing in Middletown: Christian Shaboo and Deena Nichol-Blifford, who both appeared in last spring’s production of Proof, and playwright Drew Gray, who directed Trevor, the most recent NHTC project. Otherwise, who you’ll see onstage is everybody who calls NHTC home—Megan Chenot, Erich Greene, George Kulp, Margaret Mann, Steve Scarpa, J. Kevin Smith, John Watson, Trevor Williams, enhanced by a few key non-NHTCers: Chaz Carmon, who played the animal care professional in Trevor; Chrissy Gardner, a composer and player in Broken Umbrella Theatre who plays Mary to Scarpa’s John; and Aly Miller, a child actor who plays “Sweetheart,” a girl in the audience.

Reading through the play convinced Chenot at once that it was a perfect fit for NHTC, as he could imagine a role for everyone. And “since directing is 75% casting, my work is done,” he joked. Part of the fun for regular attendees of NHTC productions is seeing what parts the familiar members take on in each new show, and it’s always a special treat when a play allows almost everyone to find something to do. Plays about towns instill a sense of community, as does the camaraderie of the New Haven Theater Company.

Middletown

By Will Eno

Directed by Peter Chenot

New Haven Theater Company

839 Chapel Street, the English Building Markets

April 27-29; May 4-6