Review of He Wrote Good Songs, Seven Angels Theatre

Anthony Newley, subject of actor/singer Jon Peterson’s dazzling one-man show, “…He Wrote Good Songs”, in its CT premiere at Seven Angels in Waterbury, was a colorful entertainer who achieved his greatest successes in the 1960s and died in 1999. I recall seeing him on variety shows in my childhood—he was unforgettable—while many were introduced to him either as a child actor playing the Artful Dodger in David Lean’s non-musical version of Oliver Twist (1948) or in his role as Matthew Mugg in the musical Dr. Doolittle (1967) for which he co-authored the songs.

Newley’s songwriting is no doubt better-known than his performances, as he co-authored—with his primary writing partner Leslie Bricusse—the songs to the cult classic film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971), which included “The Candy Man,” a song that seems inescapable. Newley and Bricusse also had their hand in the well-known James Bond movie theme “Goldfinger,” and Newley’s songs—such as “Who Can I Turn To” and “What Kind of Fool Am I”—have been successful hits for various singers, including Nina Simone and Sammy Davis, Jr.

Peterson, who first created “…He Wrote Good Songs” in 2014, was last at Seven Angels in 2009 in his show Song and Dance Man, in which he performed songs by a number of noted singers, Newley among them. The current show—its title comes from a line Newley said should be carved on his tombstone—presents Newley’s story as he himself might tell it, as a mix of his greatest hits held together by a freewheeling narrative of his life.

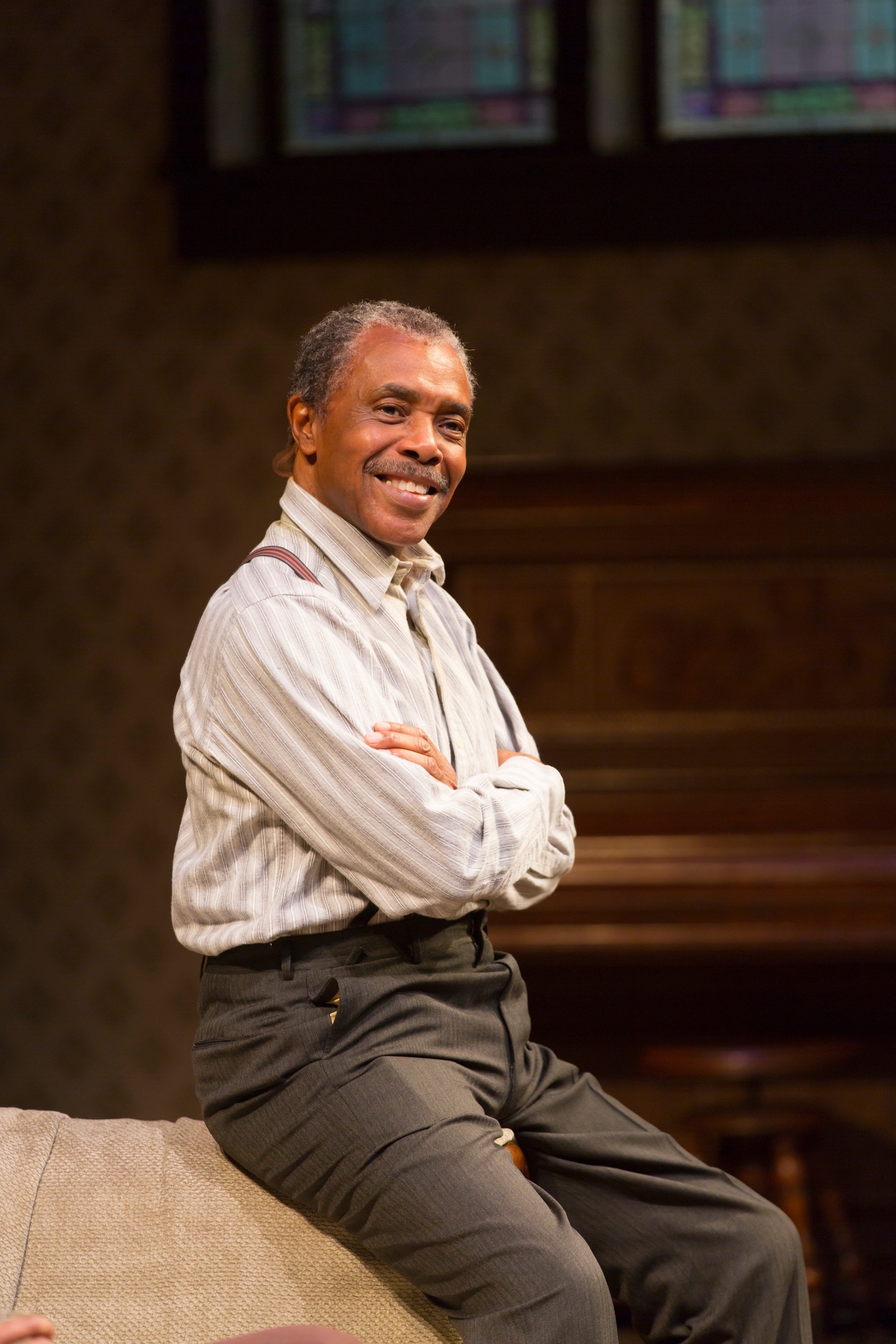

Jon Peterson as Anthony Newley

Peterson’s Newley is a consummate showman who lets us in on his somewhat checkered career and his string of marriages and infidelities with endearing charm and feckless egotism. This is the world according to Newley—or Tony—and there’s not a lot of soul-searching. It’s more like a view of life as a series of trials, where some things—a song, a show, a marriage—are successes, for awhile, and others aren’t.

The ups and downs are recounted colorfully in Peterson’s off-hand manner. We learn of Newley’s difficult childhood East of London and during the Blitz, of encouragement along the way, of early breaks, of the heady world of a child star in pre-Beatles Britain, and of his ongoing lust for the ladies, which leads him into three marriages—including to British actress Joan Collins—and a host of affairs. Newley, it seems, simply can’t turn off the charm, either in real life or on stage. There’s a lot of success, with Broadway hits and a popular Vegas show, but time keeps moving on and eventually he’s older, accused of being “a self-parody” at one point, and hailed as a genius at another. There are affecting moments, such as a reconciliation with the father who abandoned the family when Tony was a child, and lots of little Borsch-Belt-style asides served up for a chuckle—Newley paid his dues in venerable Catskill venues too.

Daniel Husvar’s set is a bright version of the tough Hackney streets where Newley’s life began, augmented by a comfy chair and clothes trunk, and Peterson runs through numerous costume changes before our eyes, always while chattering on. The songs, though not as familiar as they might be to some, are a constant delight; they are clever, catchy, and, at times, the stuff of soliloquy—“Pure Imagination,” “Oh What a Son of a Bitch I Am,” “The Joker”—while elsewhere they give us a chance to bask in Newley’s knack with a hit—“Pop Goes the Weasel.” He throws away big numbers like “Goldfinger” and “Candy Man” as if too well-known (and admits to disliking the latter), and shows an agreeable ability to take whatever life hands out. The show ends, as it must, with “What Kind of Fool Am I?,” the standard that closes Newley’s first major musical, Stop the World—I Want to Get Off, and serves as commentary on a life dogged by many foolish moves.

Peterson’s showmanship is the star here, as he gets to live out for us a life and talent that was meant for the limelight. Newley comes across as a born performer with Peterson giving an uncanny sense of the singer’s unique vocal style, in spare but effective arrangements by Bruce Barnes. And Peterson’s take-offs of those whom Newley encounters punctuate the show with artfully rendered mannerisms, making Newley an accomplished mimic as well.

Newley wrote good songs, indeed. And many are inherently theatrical in being written for shows. Peterson’s brilliant use of the songs to structure Newley’s life story makes this more than just a revue of hits while also serving to remind us of Newley’s way with a song, and way with a story. The best feature of the show is how winning Peterson is, providing the kind of interpersonal thrill that comes from finding oneself, as the saying goes, “in the palm of his hand.” It’s a showman’s show. One imagines Newley himself would be tickled by it.

“…He Wrote Good Songs”

Written and conceived by Jon Peterson

Directed by Semina De Laurentis

Musical Direction by Bruce Barnes

Vocal Arrangements and Orchestrations by Bruce Barnes and Jon Peterson

Scenic and Prop Design: Daniel Hsuvar; Lighting Design: Scott Cally; Sound Design: Matt Martin; Production Stage Manager: Elizabeth Salisch

Musicians: Musical Director/Arranger/Conductor/Pianist: Bruce Barnes; Bass/Guitar: Louis Tucci; Percussion: Mark Ryan

Seven Angels Theatre

November 3-27, 2016