Now that the International Festival of Arts & Ideas has come and gone, and even the Yale Summer Cabaret is on a hiatus until it resumes on the 11th, what is a theater person to do? One possibility is start thinking about next season.

Last week at the Long Wharf Theatre, Artistic Director Gordon Edelstein and Associate Artistic Director Eric Ting, in a conversation on stage, situated in two comfy chairs, outlined the coming 50th Anniversary Season of the New Haven theater staple, giving a nearly full house details on the process behind their choices and introducing three dramatic readings from the final three plays to be featured.

Ting, taking the role of interviewer, asked Edelstein “what is the process” in picking plays for a season. There was a charge of applause indicating that many in the audience wonder about that very question. While allowing that the process of selection is the “hardest thing,” Edelstein alluded to his 25 year experience of “picking seasons” both at Long Wharf and in Portland. He mentioned some of the logistics that affect decisions—most notably the “shrinking size of shows,” so that shows with huge casts are harder and harder to put on. And yet Edelstein said he always begins with what he “dreams of doing”—the shows he most would like to put on or see put on. “All our dreams are never realized,” he admitted, but he never loses sight of the main purpose: that a play “say something about what it’s like to be alive now.” And, throwing the question open to the audience a bit, he asked how many would agree that the future of the theater is in new writing and in finding works that appeal to a younger demographic. Most present seemed to agree heartily with this proposition.

Alluding to “the bumpy road and false starts and detours” of a process Edelstein called “complicated” and “non-predictive,” he also spoke of the three main desiderata: that the play be relevant to our local community, that it reflect the times and the country we all live in, and that the season end with a balanced budget. He added that one of the key questions each year is what the centerpiece of the season will be. This year, for the 50th anniversary of the Long Wharf Theatre, he gave that question considerable consideration, with some ideas including works by Arthur Miller, such as The Crucible, which was the first play produced at the Long Wharf, or Death of a Salesman which has never been staged there and which Edelstein would like to direct, though, he added, he felt it was “the wrong statement” at this time.

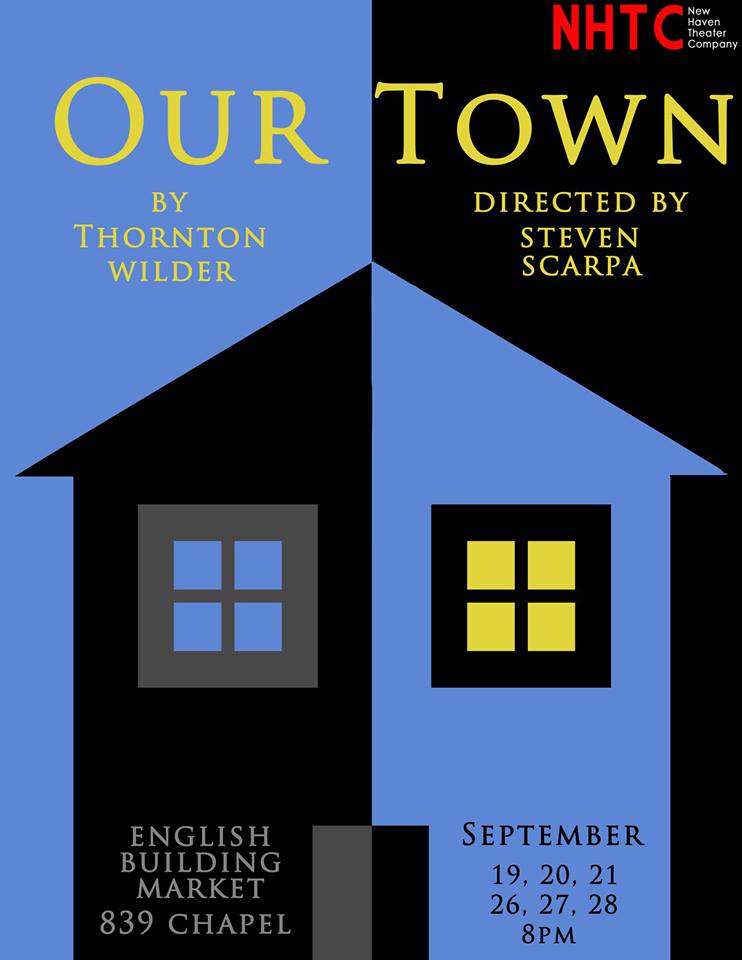

What play did fit the bill? Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, which Edelstein defended (against those who hear the title and think “high school production”) as perhaps the greatest play in the U.S. canon, a play “misunderstood” as “folksy” when in fact it was conceived by its author, who attended Yale and is buried in Hamden, as engaging with avant-garde literature of its time. What’s more, set in “all white” New Hampshire in the early 1900s, Our Town has come to seem a bit of a relic of a more homogeneous America. Edelstein intends to change all that by directed an interracial, multicultural Our Town that “looks like our town now.” He admitted to being “nervous as hell” about tackling this perhaps over-familiar chestnut with new vision as the first play of the season, then added a further wrinkle: the play would be cast using only Long Wharf “alum”—actors and crew who had worked there before. The combination of American classic, Long Wharf familiars, and a more contemporary approach should add up to an Our Town that—if you live in this town—you will not want to miss. Edelstein assured us that we “will not be disappointed.”

OUR TOWN BY THORNTON WILDER DIRECTED BY GORDON EDELSTEIN CLAIRE TOW STAGE IN THE C. NEWTON SCHENCK III THEATRE OCTOBER 9-NOVEMBER 2, 2014 PRESS OPENING: WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2014

Ting, still the interviewer, set up the next play on the bill by restating a “story” he heard that author, comedian, actor, playwright Steve Martin, upon seeing Edelstein’s version of Martin’s The Underpants at Hartford Stage last year decided that he must have the director do Martin’s Picasso at the Lapin Agile. Edelstein recounted how he met Martin at a production of The Underpants and knew that Martin felt the show had been done to perfection. Next thing he knew, he heard that Martin told the producers planning a revival of Lapin Agile that, it’s hoped, may go to Broadway for the first time, that Edelstein was the man for the job. Consequently, Long Wharf audiences will find another clever Martin comedy offered up with a sense of both its verbal absurdities and its slapstick pace, as was The Underpants. And if it does get to Broadway, you can say you saw it here first.

PICASSO AT THE LAPIN AGILE BY STEVE MARTIN DIRECTED BY GORDON EDELSTEIN CLAIRE TOW STAGE IN THE C. NEWTON SCHENCK III THEATRE NOVEMBER 26-DECEMBER 21, 2014 PRESS OPENING: WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2014

Next is the return of Dael Orlandersmith, the playwright, actress, and poet, whose works have “quite a fan base in New Haven,” where Yellowman and The Blue Album were staged at Long Wharf. Forever will be on its world premiere run, beginning in LA and stopping in New Haven en route to New York. Centered around the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, where, it so happens, American expats such as rock star Jim Morrison and renowned African-American author Richard Wright are buried among French literary figures and other notables, Forever deals with the ghosts of the past, and the sense of family—“the ones we were born into, the ones we create for ourselves”—and is, Edelstein says, Orlandersmith’s “most powerful piece yet.”

FOREVER BY DAEL ORLANDERSMITH DIRECTED BY NEEL KELLER WORLD PREMIERE STAGE II JANUARY 2-FEBRUARY 1, 2015 PRESS OPENING: WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 7, 2015

Called by the New York Times one of the best comedies of the 2013-14 season in New York, Joshua Harmon’s Bad Jews takes up the theme of legacy where two cousins, one male and one female, battle over a religious necklace, an heirloom that their late grandfather, a survivor of the Holocaust, kept concealed on his person throughout his years of captivity. The jousting between the staunchly Hebraic Daphna and her less observant cousin Liam fuels a play of the comic ties and trials of blood relations. The except on stage at the Long Wharf preview readily attested to the comic potential of Daphna’s belligerence and the hapless niceness of Liam’s non-Jewish girlfriend in the face of such superior attitudes.

BAD JEWS BY JOSHUA HARMON STAGE II FEBRUARY 18-MARCH 22, 2015 PRESS OPENING: WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2015

For the penultimate production of the season, director Eric Ting brings us a play that has its finger on the dismaying news events that continue to surface in the supposedly “post-racial” America of the Obama presidency. Kimber Lee’s brownsville song (b-side for tray) tells of the aftermath, for an interracial family, of the loss of young, engaging and promising Tray. Revealed to us in flashbacks, Tray’s life involves, in the scene enacted for us at the preview, managing a Starbucks where his step-mother, who abandoned Tray and his younger sister to their grandmother’s care, shows up, looking for a job. An “issue play on some level,” Ting said, “at heart it’s about family,” and the role it plays in dealing with tragic events and the hardships of contemporary life.

brownsville song (b-side for tray) BY KIMBER LEE DIRECTED BY ERIC TING CLAIRE TOW STAGE IN THE C. NEWTON SCHENCK III THEATRE A co-production with Philadelphia Theatre Company MARCH 25-APRIL 19, 2015 PRESS OPENING: WEDNESDAY, APRIL 1, 2015

The final play of the season, directed by Edelstein, will be the world premiere of The Second Mrs. Wilson, a play that revisits an interesting historical situation. President Woodrow Wilson’s first wife died while he was in office and he became the first president to woo and wed a woman while president. That would be interesting enough, perhaps, but the situation of the play is more pressing: not long after the wedding, Wilson suffered a stroke and was largely incapacitated. Di Pietro’s play looks at a situation in which a woman, persona non grata to the Cabinet and others trying to run the president’s administration, has to take charge in a man’s world in her husband’s stead as de facto head of the Executive Branch. In the scenes enacted at the preview, we saw Edith Boling Galt, a widow, charm the donnish president Wilson; in the second we watched her take command, delicately but firmly, of a meeting with one of the chiefs of staff. A play about the kinds of tests and resources in life that demand strong resolve, the play is relevant to the changing role of women in American politics.

THE SECOND MRS. WILSON BY JOE DiPIETRO DIRECTED BY GORDON EDELSTEIN CLAIRE TOW STAGE IN THE C. NEWTON SCHENCK III THEATRE WORLD PREMIERE MAY 6-31, 2015 PRESS OPENING: MAY 13, 2015

Subscriptions are already on sale. Single tickets will go on sale Monday, August 4. For more information about the 50th anniversary season, visit www.longwharf.org or call 203-787-4282.