The second Yale School of Drama thesis show goes up tomorrow night, Friday the 13th. Third-year director Dustin Wills, recently honored by a Princess Grace Award for his final year of study at YSD, presents his adaptation of J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. Wills, who was co-Artistic Director for the highly successful Yale Summer Cabaret of 2013, says he sought out “dark children’s stories” after realizing his plan to adapt Pinocchio was unworkable. Peter Pan, dark? Wills went to the Beinecke where he found all the various drafts of J.M. Barrie’s work on the play, which the author rewrote yearly throughout much of his life—beyond the initial stage play of 1904, An Afterthought, four years later, and the prose work, Peter and Wendy, based upon it, published in 1911. Wills, who has seen several productions, was drawn to the story, he thinks, by his former work in his home state of Texas, devising theater for underserved audiences, such as juvenile detention centers. The theme of “the Lost Boys”—the children “who fall out of prams” and are lost, until they turn up in Neverland—appealed to Wills, finding in the play a tribute to the imagination of children.

“No matter how dire things may be, nothing stops the imagination,” he said, and the story of how children might clutch onto imaginary worlds, and to youth, certainly has resonance. In his past work with children, Wills was struck by “the cleanliness of their imaginations vs. the messiness of their emotions.” The key, then, is to find a vehicle that shows the tensions within children’s imaginative compensations. Though the play is contemporary with Freud, Wills sees the text as pre-Freudian, even as he has decided to move the setting forward in time. Wills sets his production in 1917, and intends the war-time setting to inspire much of the children’s anxiety.

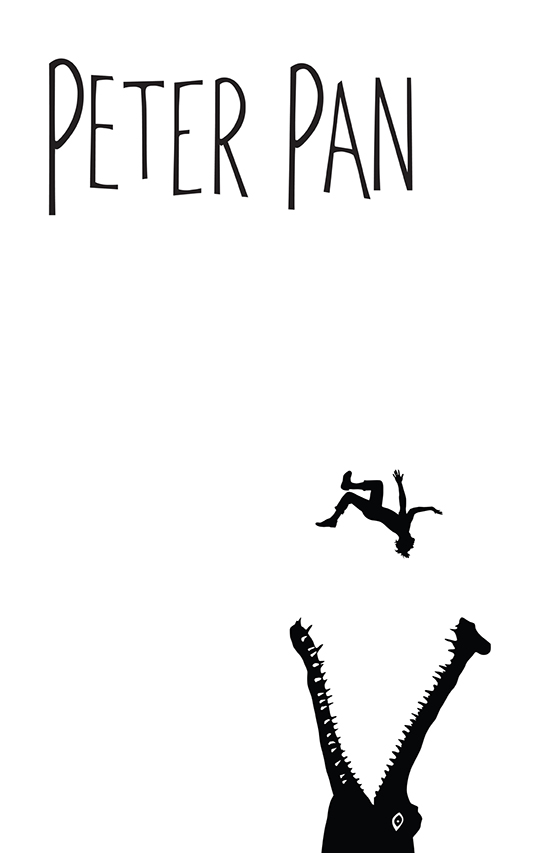

This Peter Pan is less about spectacle—no one flies, a decision not an imposed limitation—and more about themes of loss, abandonment, and the community that sustains the children in Neverland. With a cast of thirteen, the show is large, and features what Wills calls “ruin porn” in its set—the picturesque qualities of the dilapidated and partially destroyed, showing the grim realities the children have to work with. In Wills’ conception, the children—orphans all—are putting on the show in an effort to find homes among would-be adopting families. Thus one can expect that the elements of showmanship—as Wills’ actors play children acting—will underscore the tenuous relation between the children’s imagination and the audience’s willful suspension of disbelief.

The first thing, then, is that we believe in the children as children. Wills said he has coached his actors to be themselves as children—or early teens at most—as much as possible. The cast, Wills said, became very close very quickly, and “everybody worked really well together from the start,” which has permitted the show to do a full tech run-through well ahead of schedule. And that’s even with a few setbacks, such as Wills himself being sick when the rehearsals began, and losing the actor originally cast as Hook due to an injury during a classroom workshop.

The prospect of actors behaving as younger versions of themselves who then take on the roles in the “Peter Pan” show the orphanage is putting on—including the Darling home as well as Neverland—permits the kind of interesting double-vision found in play-within-a-play situations. The text of Wills’ show, then, is not a version of Peter Pan that anyone will have seen before. His researches led Wills to “grab from all sources,” including a screenplay for a silent film that Barrie composed, as well as incorporating a line that has always been cut from the play, but which Wills restores.

For Wills, the play, in its Edwardian setting, has always been to some degree about “what childhood means.” Granted, there are highly un-PC aspects of the play Barrie wrote—with Indians as savages and girls as domestic servants in-waiting—but Wills wants to retain those aspects to indicate how childish imaginations work. The question this should raise, among modern—adult—audiences (Wills’ show is not designed as an entertainment for children) is “what did I grow up on?”

Wills stresses how all of us, in our fantasies, incorporate the materials that have left their mark on our imaginations, the images that arise from whatever dimly remembered tales and films and shows and cartoons of our youth. Certainly, for generations in the U.S. since the fifties, the prevailing common denominator has been Disney, but in earlier eras the stereotypes of the day—in children’s adventure stories—would’ve done that work. Peter Pan and his adventures, then, becomes the kind of tale children themselves might invent as a defense against the grown-up world of war and chaos, even as they invent manageable villains—a pirate (Captain Hook)—and an exotic maiden (Tiger Lily), a fairy (Tinkerbell), and a mother figure (Wendy), for sentimental reasons.

In Wills’ production we may hope to see, rescued from the preciousness of Disney and the more upbeat aspects of Broadway, a Peter Pan grown-up at last.

Yale School of Drama presents Peter Pan Directed and adapted by Dustin Wills

Yale University Theatre December 13-19, 2013