Yale Cabaret Season 51 is now just a treasured memory, brought to mind again by my yearly recap of some highlights of what went down. All cordial thanks to the departing team of Co-Artistic Directors Molly FitzMaurice and Latiana “LT” Gourzong and Managing Director Armando Huipe for a lively season abetted by their welcoming presences.

Departing team 51: Armando Huipe, Molly FitzMaurice, Latiana “LT” Gourzong

In hitting the highlights, I cite my “top five” in each category in order of appearance—except my favorite, which comes last.

The pre-existing plays I was most glad to see: (Cab 2) Fade by Tonya Saracho, directed by Kat Yen: a character study in the context of gender inequalities and upward mobility and claiming cultural kinship in the workplace; (Cab 5) Agreste (Drylands) by Newton Moreno, translated by Elizabeth Jackson, directed by Danilo Gambini: a folkloric story of sexual identity and the true meaning of love and sacrifice; (Cab 10) School Girls; Or the African Mean Girls Play by Joceyln Bioh, directed by Christopher D. Betts: a lively treatment of the teen rivalry genre with many knowing details; (Cab 11) The Rules by Charles Mee, adapted by Dakota Stipp, Zachry J. Bailey, Alex Vermillion and Evan Hill, directed by Zachry J. Bailey: a quizzical upbraid of cultural and aesthetic norms and the tired conformities we live by; and . . . (Cab 1) The Purple Flower by Marita Bonner, directed by Aneesha Kudtarkar: a mythopoetic tale of racism as a curse of biblical proportions, requiring epic heroism.

Plays from Yale School of Drama authors: (Cab 8) Taking Warsan Shire Out of Context on the Eve of the Great Storm by Christopher Gabriel Nuñez, directed by Oliva Plath: a futuristic tale, both ironic and vulnerable, about a coterie of brainiacs in a frozen waste, finding love; (Cab 13) Lenny’s Fast Food Kids Gang by Angie Bridgette Jones, directed by Alex Keegan: a very sharp and entertaining take on how “televised” our lives are, and how that undermines real connections; (Cab 15) Avital by Michael Breslin, with Amandla Jahava and Zoe Mann, directed by Michael Breslin: academic privilege is never usually this funny but it’s also, y’know, sad; (Cab 18) Alma by Benjamin Benne, directed by Cat Rodriguez: a reminder that equality in America is always a work in progress, requiring constant vigilance; and. . . (Cab 14) Novios by Arturo Luis Soria III, directed by Amandla Jahava and Sohina Sidhu: a workplace love story among immigrants from various points of origin, forging an Americas dream.

Scenic Design: (Cab 1) The Purple Flower, Lily Guerin: the detritus of civilization framing two distinct worlds; (Cab 3) The Light Fantastic, Stephanie Bahniuk: a homey space grown creepy with uncanny happenings; (Cab 17) Fireflies, Anna Grigo: a kitchen aching with nostalgia; (Cab 18) Alma, Elsa GibsonBraden: a convincingly homey apartment, with kitchen; and . . . (Cab 14) Novios, Gerardo Díaz Sánchez: a restaurant kitchen as the center of the universe.

Lighting Design: (Cab 3) The Light Fantastic, Emma Deane: effects for the sake of suspense and surprise; (Cab 5) Agreste (Drylands), Nic Vincent: poetic and impressive, suggesting the passing of time; (Cab 14) Novios, Nic Vincent: a range of moods in the same locale; (Cab 15) Avital, Ryan Seffinge: playfully creating a unique performance space; and . . . (Cab 17) Fireflies, Riva Fairhall: the light streaming across the kitchen late in the play nailed it for me.

Projection Design: (Cab 4) Untitled Ke$ha Project, Elena Tilli: fun on all fronts, a multi-media party; (Cab 5) Agreste (Drylands), Yaara Bar: a subtle and transcendent effect; (Cab 11) The Rules, Camilla Tassi & Elena Tilli: scenic, abstract, a visual tapestry; (Cab 15) Avital, Erin Sullivan & Matthias Neckermann: when life becomes a cartoon and a newsfeed; and . . . (Cab 17) Fireflies, Nicole E. Lang: the skyscapes to the side were effective, but when they came into the kitchen…

Sound Design: (Cab 1) The Purple Flower, Liam Bellman-Sharpe, Emily Duncan Wilson: otherworldly and direct, enabling a protracted myth; (Cab 3) The Light Fantastic, Andrew Rovner: uncanny and surprising, enabling suspense; (Cab 4) Untitled Ke$ha Project, Megumi Katayama: propulsive and upbeat, enabling voice and dance; (Cab 17) Fireflies, Kathy Ruvuna: unsettling and dark, inspiring foreboding; and . . . (Cab 11) The Rules, Dakota Stipp: inventive, interactive, creating an inspired environment.

Use of Music: (Cab 5) Agreste (Drylands), directed by Danilo Gambini: when Ilia Isorelýs Paulino sang “Eye on the Sparrow”; (Cab 7) It’s Not About My Mother, directed by Sam Tirrell: Stevie Nicks incarnate! and I was never much of a fan; (Cab 14) Novios, directed by Amandla Jahava and Sohina Sidhu: kitchen percussion, among other dance measures; (Cab 15) Avital, directed by Michael Breslin: from ABBA to Barbra and on; and . . . (Cab 4) Untitled Ke$ha Project, directed by Latiana “LT” Gourzong: I don’t know this music, gotta admit, but “Hymn” and “Tik Tok” worked, and I’d rather watch a dance-off than a karaoke contest…

Original Music: (Cab 8) Taking Warsan Shire Out of Context on the Eve of the Great Storm, Aaron Levin, Composer: my favorite aspect of this oddly challenging play; (Cab 16) Exit Interview, Christopher Gabriel Núñez aka Anonymous (And.On.I.Must), Beats by The Brainius: a surprising range of moods, from aggressive to vulnerable to uplifting; (Cab 16) Untitled semi-improvised dance/music piece, Sarah Xiao and Liam Bellman-Sharpe: no, I don’t really know what it was aiming for, but I was fascinated the entire time; (Cab 16) UNAMUSED: a feminist musical fantasia…, Book, Music & Lyrics by Sam Linden: a cute feminist musical fantasia; and . . . (Cab 9) The Whale in the Hudson, Liam Bellman-Sharpe, Music Director; Brad McKnight, Music: an utterly charming use of music and song, in an epic kids’ mystery based on real life.

Costumes: (Cab 1) The Purple Flower, Mika H. Eubanks: sometimes a character is in a hat, but it’s got to be the right hat; (Cab 4) Untitled Ke$ha Project, Yunzhu Zeng: fanciful, fun, and the robe “LT” wore was worthy a prize-fighter; (Cab 5) Agreste (Drylands), April M. Hickman: restrained, austere, and evocative of a range of places; (Cab 11) The Rules, April Hickman & Yunzhu Zeng: the transformation of Arthur was simply stunning; and . . . (Cab 17) Fireflies, Mika H. Eubanks, with hair by Earon Nealey: it’s rare to have costume changes like this in a Cab show, and all so appropriate.

Acting Ensemble: (Cab 5) Agreste (Drylands), Abubakr Mohamed Ali, Rachel Kenney, Ilia Isorelýs Paulino: incredibly effective round-robin sequences and intense character studies; (Cab 10) School Girls; Or the African Mean Girls Play, Moses Ingram, Wilhemina Koomson, Kineta Kunutu, Gloria Majule, Alexandra Maurice, Vimbai Ushe, Adrienne Wells, Malia West: some are actors, some aren’t but this cast created a vivid dynamic, funny and mean and lovable; (Cab 13) Lenny’s Fast Food Kids Gang, Holiday, Daniel Liu, Bre Northrup, Julian Sanchez, Madeline Seidman, Malia West: a range of actors trying to figure out who they really are and were; (Cab 14) Novios, Nefesh Cordero Pino, Raul Díaz, Christopher Gabriel Nuñez, John Evans Reese, Gregory Saint Georges, Devin White, Jecamiah M. Ybañez: bilingual, multiracial, with a striking group energy and individual interactions; and . . . (Cab 3) The Light Fantastic: Stephen Cefalu, Jr., Noah Diaz, Gregory Saint Georges, Moses Ingram, Doireann Mac Mahon, Anula Navlekar, Adrienne Wells; a dream cast in a somewhat unmanageable tale of fate and second chances (kudos to director Molly FitzMaurice for bringing this to the Cab).

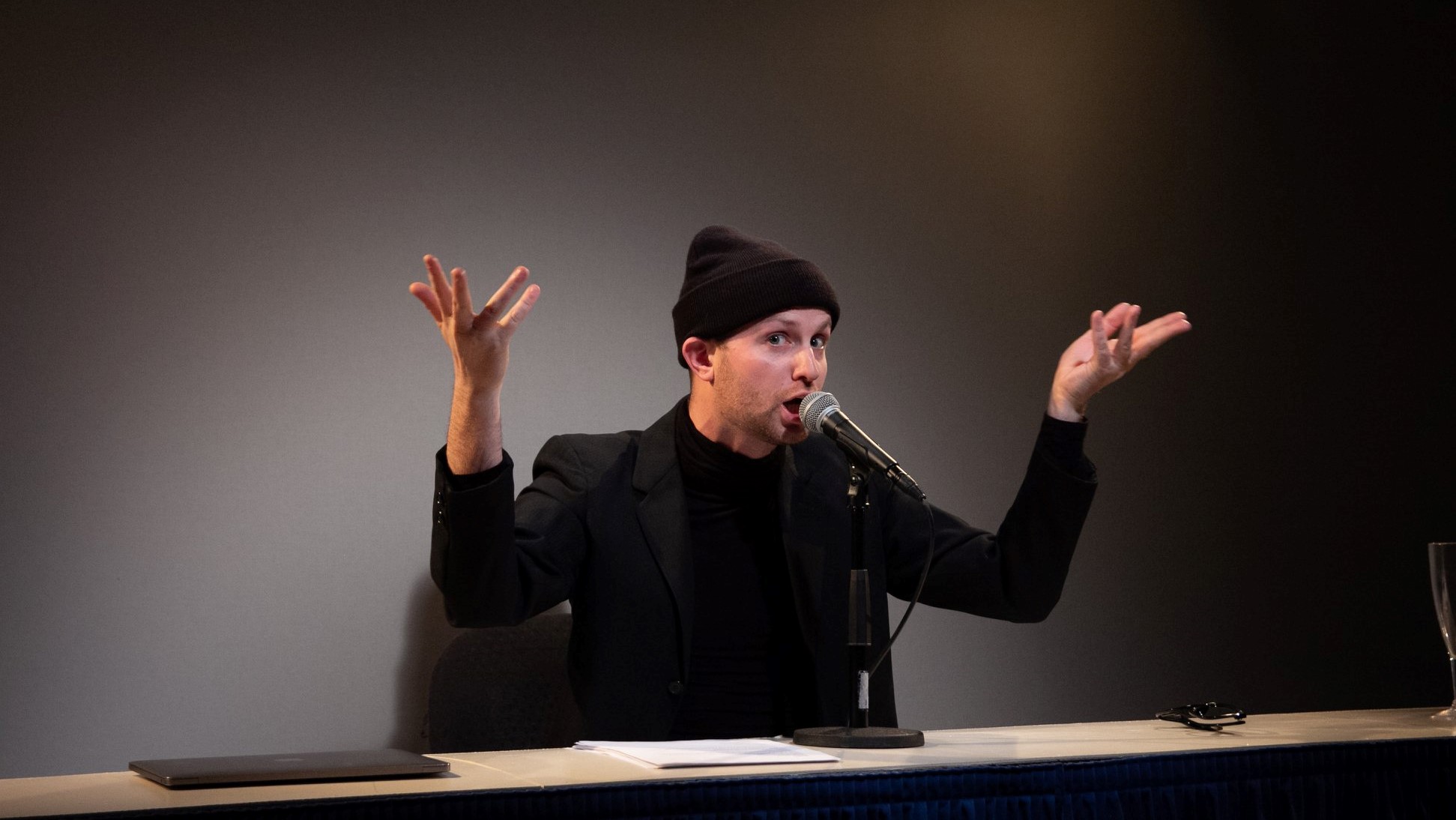

Actors: (Cab 2) Fade, Dario Ladani Sánchez: a reserved working guy with something to hide and something to lose; (Cab 5) Agreste (Drylands), Abubakr Mohamed Ali: an elusive, mysterious figure, full of quiet charisma, and a priest out of his depth; (Cab 14) Novios, Jecamiah M. Ybañez: the loose cannon, a man of passion and talent making a big discovery; (Cab 17) Fireflies, Manu Kumasi: the nuances of a man of faith and progress who can still be a bully at home; and . . . (Cab 15) Avital, Michael Breslin: performance as provocation and seduction delivered with fragile irony, and funny as hell.

Michael Breslin in Avital, Yale Cabaret

Actresses: (Cab 2) Fade, Juliana Aiden Martínez: a mercurial woman on the way up, and, in general, writers are not to be trusted; (Cab 7) It’s Not About My Mother, Amandla Jahava: holy fuck, whatever she’s got—figure out how to bottle and sell it! (Cab 10) School Girls; Or the African Mean Girls Play, Moses Ingram: you aren’t supposed to like her, but then you do; a performance that stayed with me; (Cab 18) Alma, Ilia Isorelýs Paulino: a powerful showcase as all the mothers everywhere, just trying to stay here; and . . . (Cab 1) The Purple Flower and Fireflies (Cab 17), Ciara Monique McMillian: in the first, she was all the men; in the second, she was all woman, in both cases, memorable.

Ciara Monique McMillian in Fireflies, Yale Cabaret

Directing: (Cab 1) The Purple Flower, Aneesha Kudtarkar: a varied cast played essentially by two actors in an amazing concert of types and archetypes; (Cab 5) Agreste (Drylands), Danilo Gambini: a bracingly rhythmic approach, full of portent; (Cab 10) School Girls; Or the African Mean Girls Play, Christopher D. Betts: a play about intergenerational group dynamics brought off with great ensemble work; (Cab 11) The Rules, Zachry J. Bailey: an offbeat highpoint of the season in its amorphous approach to theater; and . . . (Cab 14) Novios, Amandla Jahava & Sohina Sodhu: two third-year actors direct with great feeling a large cast at work, at love, and in strife with their place in life.

For overall Productions:

Cab 1: A thoughtful and poetic play, unproduced and mostly forgotten, delivered with consummate skill as a challenging opening to Cabaret 51: The Purple Flower by Marita Bonner; conceived by Mika H. Eubanks and Aneesha Kudtarkar; directed by Aneesha Kudtarkar; Producer: Caitlin Crombleholme; Co-Dramaturgs: Christopher Audley Puglisi, Sophie Siegel-Warren; Stage Manager: Olivia Plath; Scenic Designer: Lily Guerin; Lighting Designer: Nicole E. Lang; Sound Designer: Liam Bellman-Sharpe, Emily Duncan Wilson; Costume Designer: Mika H. Eubanks; Movement Director: Leandro Zaneti; Technical Director: Alex McNamara;; Cast: Ciara Monique McMillian, Adrienne Wells, Devin White, Patrick Young

Cab 11: What do you do when the avant-garde becomes “classic” and then declassé: make new rules? An exhilarating production, “old school” Cab: The Rules by Charles Mee; adapted by Dakota Stipp, Zachry J. Bailey, Alex Vermillion, Evan Hill; directed by Zachry J. Bailey; Producers: Caitlin Crombleholme & Eliza Orleans; Dramaturgs: Evan Hill & Alex Vermillion; Stage Manager: Sam Tirrell; Scenic Designer: Sarah Karl; Lighting Designer: Evan Christian Anderson; Sound Designer & Composer: Dakota Stipp; Costume Designers: April Hickman & Yunzhu Zeng; Projection Designers: Camilla Tassi & Elena Tilli;; Technical Director: Mike VanAartsen; Cast: Robert Hart, David Mitsch, Adrienne Wells

Cab 14: Poetic, mysterious, and as vivid as real life, full of fun, tension, and passion—and it was only the first half!: Novios by Arturo Luis Soria III; directed by Amandla Jahava & Sohina Sidhu; Producer: Estefani Castro; Dramaturg: Nahuel Telleria; Stage Manager: Fabiola Feliciano-Batista; Choreographer & Intimacy Coach: Jake Ryan Lozano; Scenic Designer: Gerardo Díaz Sánchez; Costume Designer: Matthew Malone; Lighting Designer: Nic Vincent: Projection Designer: Sean Preston; Sound Designer: Andrew Rovner; Technical Director: Martin Montaner V.; Cast: Nefesh Cordero Pino, Raul Díaz, Christopher Gabriel Nuñez, John Evans Reese, Gregory Saint Georges, Devin White, Jecamiah M. Ybañez

Cab 17: The play itself is a bit overwrought in its dramatic arc—but the cast and crew upped the ante for Cab shows: Fireflies by Donja Love; directed by Christopher D. Betts; Producer: Dani Barlow; Dramaturg: Sophie Greenspan; Stage Manager: Zachry J. Bailey; Scenic Designer: Anna Grigo; Costume Designer: Mika H. Eubanks; Projection Designer: Nicole E. Lang; Sound Designer: Kathy Ruvuna; Lighting Designer: Riva Fairhall; Technical Directors: Chimmy Anne Gunn & Francesca DeCicco; Fight Choreographer: Michael Rossmy; Hair: Earon Nealey; Cast: Manu Kumasi, Ciara Monique McMillian

And…

Cab 5: Part folktale, part mystery play; a magisterially achieved story of transformation and the miracle of love—regardless of what kind of body it wears: Agreste (Drylands) by Newton Moreno, translated by Elizabeth Jackson; directed by Danilo Gambini; Producer: Jaime F. Totti; Dramaturg: Maria Inês Marques; Stage Manager: Cate Worthington; Set Designers: Alexander McCargar and Sarah Karl; Costume Designer: April M. Hickman; Lighting Designer: Nic Vincent; Sound Designer: Emily Duncan Wilson; Projections Designer: Yaara Bar; Technical Director: Martin Montaner V.; Cast: Abubakr Mohamed Ali, Rachel Kenney, Ilia Isorelýs Paulino

Special honorary citations: Cabaret Heroes: working on three shows in a season at the Cab is not uncommon, so most of these have surpassed that number, and/or worked in varied positions: Ciara Monique McMillian appeared in three shows in lead roles; Amandla Jahava appeared in two shows, contributed content to one, and co-directed a third; Kat Yen directed two shows, providing sound design for one, and wrote and performed a third; Stephanie Bahniuk worked as a set designer for two shows, costume designer on a third, and co-conceived a fourth; April Hickman designed costumes for three shows and co-conceived a fourth she appeared in; Olivia Plath worked as stage manager on three shows and directed a fourth; Zachry J. Bailey worked as stage manager on three shows and directed and co-adapted a fourth; Liam Bellman-Sharpe was sound designer on two shows, music conductor on a third, and was co-conceiver, composer, and performer in a fourth; Adrienne Wells acted in four shows and provided a voice-over for a fifth; Mika H. Eubanks was costume designer on four shows and co-conceived two others, appearing in one.

The Yale Cabaret has entered its sixth decade, going strong! Great thanks and grateful acknowledgment to all who took part and who came out for the shows.

Next year’s team, for Yale Cabaret 52, are Co-Artistic Directors Zachry J. Bailey, Brendan Burton, Alex Vermillion, and Managing Director Jaime F. Totti; they’ll take over after the long-awaited return of the Yale Summer Cabaret, or “Verano,” with Co-Artistic Directors Danilo Gambini and Jecamiah M. Ybañez and Managing Director Estefani Castro, which will feature: Euripides’ Bakkhai, in Anne Carson’s translation, directed by Danilo Gambini, June 6-15; The Conduct of Life by María Irene Fornés, directed by Jecamiah M. Ybañez, June 20-29; The Swallow and the Tomcat by Jorge Amado, adapted and directed by Danilo Gambini, July 18-27; and Latinos Who Look Like Ricky Martin by Emilio Rodriguez, directed by Jecamiah M. Ybañez, August 8-17.

Yale Cabaret

September 2018-April 2019