Review of The Piano Lesson, Hartford Stage

Of August Wilson’s ten-play American Century Cycle, tracing African-American life through each decade of the 20th century, The Piano Lesson, which won the Pulitzer in 1990, is one of the most popular, and in this very handsome and involving production at Hartford Stage, directed by Jade King Carroll, it’s easy to see why. The show has clear themes of haunting and legacy, boasts enthralling musical numbers that help create the sense of solidarity among characters with disparate intentions, and offers its actors lots of room to stretch out in, discovering nuances of character in dialogues that seem to move backward—into a past that hovers over everyone here—and forward—into a future still to be forged—simultaneously. It’s wonderfully rich writing, and Wilson is in no hurry to get the play where it’s going. These characters need to steep awhile before the tensions can get ironed out. The fact that most do helps as well.

Boy Willie (Clifton Duncan) (photo: T.. Charles Erickson)

Boy Willie (Clifton Duncan) shows up unexpectedly at the house his sister Berniece (Christina Acosta Robinson) shares with their uncle Doaker (Roscoe Orman) and her daughter Maretha (Elise Taylor) in the Hill Section of Pittsburgh. Accompanied by his friend Lymon (Galen Ryan Kane), Willie's intention is to sell a truckload of watermelons. Boy Willie’s secondary intention, he soon reveals to his uncle, is to sell an heirloom piano that sits in the parlor of the house. With the money from both sales, together with what he has saved, he plans to buy land that his family worked, first as slaves and then as share-croppers, back home in Mississippi.

Doaker, Berniece, and even Lymon have no interest in returning to the South, but Boy Willie’s dream of being a man of property in the town where his ancestors were treated as property is the main tension driving the play. But the piano has been decorated with the carved faces of ancestors—including Willie and Berniece’s grandmother and father, sold to pay for the piano—and polished with their blood. As such, the fate of the piano becomes an allegory about the relation of the present to the past and the question of what should constitute a basis for identity—historical, racial, familial.

Boy Willie (Clifton Duncan) and Lymon (Galen Ryan Kane) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

To compare the production to the Yale Rep’s revival in 2011, directed by Liesl Tommy, the main difference, noticed at once, is how much better the Hartford Stage playing space delivers the feel of a real house, one that gives the audience very direct access to the action. Alexis Distler, who designed the Delaney sisters incredibly detailed home last season for Long Wharf’s Having Our Say (also directed by Jade King Carroll) has created a space for the Charles family that looks homey and accommodating and even features a glimpse of a neighboring house, styled after Wilson’s own family home on Bedford Avenue in Pittsburgh. “The Hill” is home to most of the plays in Wilson’s cycle and the Hartford production maintains a sense of place that surrounds the action.

Key moments, like the four men—Willie, Lymon and Doaker are joined by the latter’s brother Wining Boy (Cleavant Derricks)—bonding in a blues learned from doing hard labor at Parchman Farm in Mississippi, are placed front and center and are fully involving; the effects of the presence of Sutter’s ghost—the death, from falling down a well, that leaves the land free for Willie to buy—are subtle but strong in the final confrontation.

Berniece (Christina Acosta Robinson), Wining Boy (Cleavant Derricks) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

The development of this production shows a distinctive grasp of each character’s trajectory: Berniece, harsh and unwelcoming, becomes a figure of strength and pathos as we realize all she has lost and all she wants to hold onto; Boy Willie, essentially a smooth-talker looking out for number one, gradually gains stature as he speaks of how he wants to turn the tables and overcome his family’s past; Doaker, with his speech recalling the piano’s history, is an older and wiser figure, removed from the fray, until his threat to protect the piano brings out an almost forgotten strength of will; Lymon, at first a laconic sidekick for Boy Willie, becomes capable of enough romantic eloquence to sway Berniece to tenderness; and Wining Boy, a piano player tired of being a piano player, commands a towering voice in his rendition of a song he wrote for his wife, now deceased (Baikida Carroll, composer).

Lymon (Galen Ryan Kane) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

One of the most beguiling aspects of Wilson’s drama is how the characters interact with one another. Though at times at loggerheads, they still have a lot of shared experiences, assumptions, and expectations. They are mostly related, and the others they know all about—like Avery (Daniel Morgan Shelley), an elevator-operator who aspires to be a preacher and also aspires to be Berniece’s husband, whom Boy Willie remembers well and vice versa. Wilson’s deep sense of how these folk scrape along and make plans and entertain their dreams—such as Lymon’s hope, inspired by Wining Boy, that a silk suit and sharp shoes will immediately earn him respect and female interest—makes for many revealing moments of truth.

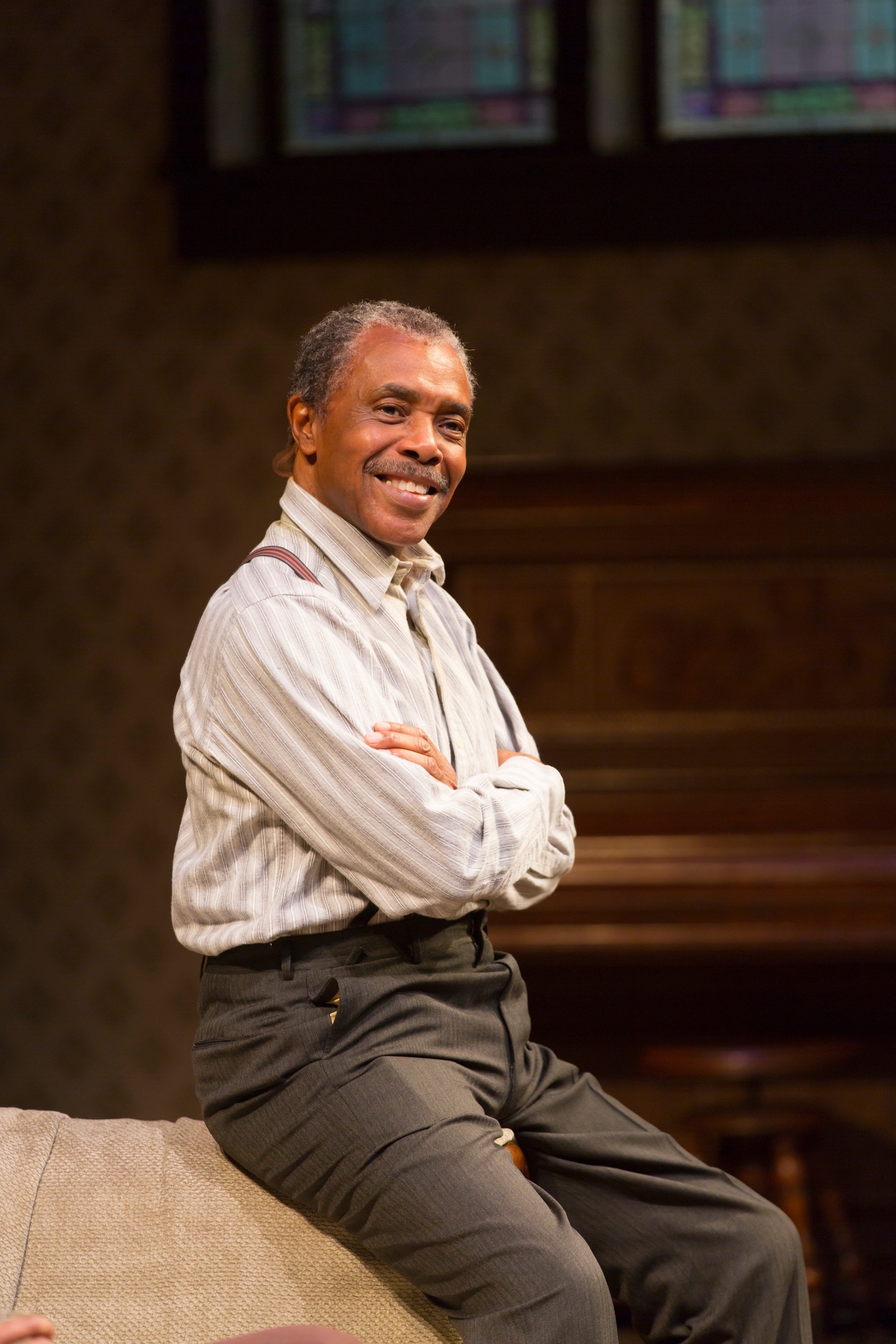

Doaker (Roscoe Orman) (photo: T. Charles Erickson)

Of special mention should be Orman’s Doaker, whose speech patterns and silent reactions conjure a character somewhat in hiding from his own past, and Kane’s Lymon, whose strong, silent-type manner makes him memorable as a figure key to Wilson’s intentions in the play: to depict the newcomer in the North, capturing the contrast between the more gentlemanly southerners and more callous northerners. There’s also the sense of a grand style fading as Wining Boy helps us imagine figures of the glamorous Twenties becoming has-beens in this post-Depression era world. As the spatting brother and sister, Clifton Duncan and Christina Acosta Robinson register well the deep familiarity and stubborn differences that make all the characters seem peripheral to the struggle of the family’s younger generation—now in its thirties—to cope with its past and find its future.

Through it all the star of the show is Wilson’s ear for the rhythms of speech, rendered well by this top-notch cast.

August Wilson’s

The Piano Lesson

Directed by Jade King Carroll

Scenic Design: Alexis Distler; Costume Design: Toni-Leslie James; Lighting Design: York Kennedy; Sound Design: Karin Graybash; Wig Design: Robert-Charles Vallace; Composer: Baikida Carroll; Music Director: Bill Sims, Jr.; Fight Director: Greg Webster; Dialect Coach: Ron Carlos; Dramaturg: Fiona Kyle

Cast: Toccarra Cash, Cleavant Derricks, Clifton Duncan, Galen Ryan Kane, Roscoe Orman, Christina Acosta Robinson, Daniel Morgan Shelley, Elise Taylor

Hartford Stage

October 13-November 13, 2016