Review of Native Gardens, Westport Country Playhouse

At the conclusion of Voltaire’s satirical narrative Candide, the protagonist reflects that the only way to find happiness in this volatile and uncertain world is “to tend one’s own garden.” Karen Zacarías’ bright situation comedy, Native Gardens, playing at Westport Country Playhouse through March 8, directed by Joann M. Hunter, suggests—comically—that tending a garden may come with its own stress and political tensions.

Frank Butley (Adam Heller), Virginia Butley (Paula Leggett Chase), Tania Del Valle (Linedy Genao), Pablo Del Valle (Anthony Michael Martinez) in Native Gardens, Westport Country Playhouse; photo by Carol Rosegg

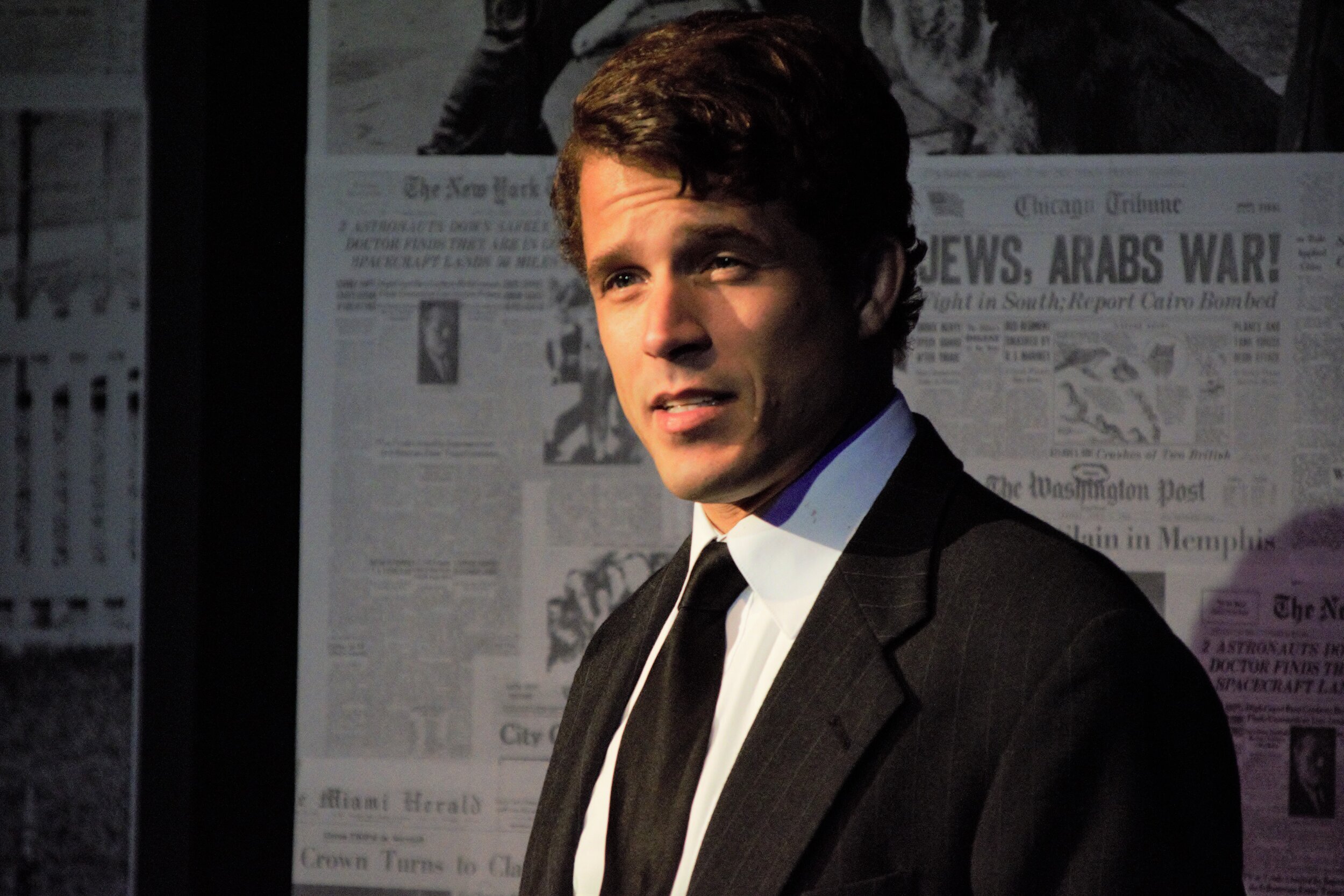

Anna Louizos’ sumptuous set confronts us with two different backyards, situated in an upscale neighborhood in Washington DC. On our right, a well-appointed brick house with a stone porch on the back and a very well-tended garden full of bright blooms; on our left, a less maintained house, with siding, overhung by the leaves and branches of a large tree, and a yard with a simple table and chairs near an ivied fence. On the right live the Butleys, Virginia (Paula Leggett Chase) and Frank (Adam Heller), gray-haired, affable, Republican; Frank tends his garden assiduously, desperate to do better than Honorable Mention in the yearly neighborhood competition. On the left, live Tania Del Valle (Linedy Genao), a pregnant doctoral student, and her husband Pablo (Anthony Michael Martinez), a Chilean immigrant eager to make partner at the law firm where he works. They are the new owners of this fixer-upper, and we learn that Tania is very committed to using only indigenous plants in her gardening as she looks askance at Frank’s fussy, imported flowers and shrubs.

Even if the clash here were only about the do’s and don’ts of horticulture, the confrontation between these two couples would likely spin through a number of push-button topics designed to demonstrate the perils of neighborliness in ideologically fraught times. Early on, the talk establishes that Tania’s “people” have been on the North American continent for ages, that she is from New Mexico, not Mexico, and that Pablo hails from a world of chauffeur-driven limos and private schools. Frank and Tania seem to bond on the importance of gardening, even if their ideal gardens are very different; Virginia attempts to find common cause with Pablo by asserting that being a woman in a male preserve such as engineering—her field—is comparable to being a non-white man trying to climb the ladder today.

Pablo Del Valle (Anthony Michael Martinez), Frank Butley (Adam Heller), Tania Del Valle (Linedy Genao) in Native Gardens, Westport Country Playhouse; photo by Carol Rosegg

Zacarías’s dialogue lets each character get across an individual perspective but without drawing major fault lines. Everyone is trying to be likeable. The real disruption occurs not for reasons of taste, or background or even political affiliation. When the Del Valles decide the chain-link fence must go, to be replaced by a wooden one that the Butleys welcome, a glance at the map of their plot indicates that their property line actually extends about two feet into Frank’s garden. Now, it’s time to bring in the rhetorical big guns—about land-grabs, borders, and squatter’s rights, about time-honored stewardship, the rule of law, and old privilege vs. new ambition.

Zacarías works in just enough issues-talk to indicate how our larger cultural surround inflects even our most trivial occupations, and Joann M. Hunter’s direction keeps everything on an even keel, so that we are intrigued more than confronted by the situation. Mention should be made too of how well the silent “workers” are played by Horacio “Joe” Cardozo and Brianna Parkin, whose very presence shows how necessary an underclass is to any upper-class assertions.

Pablo Del Valle (Anthony Michael Martinez), Frank Butley (Adam Heller) in Native Gardens, Westport Country Playhouse; photo by Carol Rosegg

All the drama plays out with notable give-and-take—as for instance, the escalating late-night fracas between Frank and Pablo that is not without a certain self-consciousness, or the “women make nice better than men” assumptions that goad Virginia and Tania into a talk that goes delightfully off the rails. Throughout, there is a fairly nuanced sense of how these two contemporary households differ, and, most usefully, how the perspective of being near retirement vs. up-and-coming plays into the situation.

The problem, which gets uglier and less resolvable as it goes on, receives a dramatic turn that could be called “bambina ex machina.” The epilogue might seem corny in its “can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” cheer, but Zacarías seems to assume that, if we can suffer being ribbed for our eagerness to assert our distinct identities and preferences and assumptions, we can also be ribbed for our hope for happy endings. The script is resolutely fun, but rarely really funny.

Tania Del Valle (Linedy Genao), Frank Butley (Adam Heller), Virginia Butley (Paula Leggett Chase) in Native Gardens, Westport Country Playhouse; photo by Carol Rosegg

The cast acquit themselves well, all very believable in their roles, bringing enough particularity to seem individuals rather than types. As Pablo, Anthony Michael Martinez doesn’t seem yet the slick lawyer we might expect him to become, and his effort at domestic tranquility requires much input from his wife. He seems to spend most of his time flustered. Linedy Genao’s Tania has a freshness and youth that might make us think she’ll be docile and meek, but guess again; when she cusses out Virginia in Spanish we have a glimpse of how risky it is to cross her. As Frank, Adam Heller seems a truly likeable guy’s guy, the type that inhabited many a sitcom where a family is presided over by a sometimes wise, sometimes silly successful white male (early on, Tania quips that the Del Salles are “living next-door to the Dick Van Dyke Show”); he does go on a bit too much about his damn garden contest, but that just shows he’s used to getting his way. The star of the show is Paula Leggett Chase’s Virginia, full of arch mannerisms and meaningful silences and comic timing; we see how much having an argument with these newcomers gets her juices flowing and we imagine Virginia hasn’t been this turned-on in years.

Frank Butley (Adam Heller), Virginia Butley (Paula Leggett Chase) in Native Gardens, Westport Country Playhouse; photo by Carol Rosegg

The set, costumes, lighting, incidental music between scenes are all superb—and all serve well the expectation that theater show us a reasonable facsimile of our lives and times. Playing in Westport, we might find we do indeed recognize these characters and, with the world as dictated by Washington DC becoming daily a more alarming concern, we might find a trip back to the relative stabilities of the late twenty-teens reassuring. As Tania allows at one point, their neighbors, though Republicans, “are people too.”

Native Gardens

By Karen Zacarías

Directed by Joann M. Hunter

Set Designer: Anna Louizos; Costume Designer: David C. Woolard; Lighting Designer: Charlie Morrison; Sound Designer: John Gromada; Prop Supervisor: Anna Dorodnykh; Production Stage Manager: Abigail Zaccari; Assistant Stage Manager: Willy Kinch; Production Assistant: Mariana Jennings

Cast: Paula Leggett Chase, Linedy Genao, Adam Heller, Anthony Michael Martinez

Westport Country Playhouse

February 18-March 8, 2025