Review of Father Comes Home from the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3, Yale Repertory Theatre

The ancient Greek stories that surround the siege of Troy are many and varied. Some are stories of fierce battle, some are stories of defection from battle, of leave-taking and of homecoming, often to violence or betrayal. Some are stories of clever subterfuge, and one of the all-time greatest a scene in which a king in mourning kisses the hands of and shares a meal with the man who killed the king’s beloved son. These stories have resonated for centuries throughout the literature originating in or derived from Europe.

The cast of Father Comes Home from the Wars, Part 1, at Yale Repertory Theatre (photos by Joan Marcus)

Suzan-Lori Parks’ Father Comes Home from the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 keeps that literary tradition in mind in a trilogy of plays situated at the time of the American Civil War. The idea of creating theater equal to a mythological sense of the battle over slavery in the States—in plays focusing primarily on the enslaved—is dauntingly brilliant. Significantly, the rhythms of Parks’ poetic language invite epic considerations and give her characters a stylized naturalism that gestures to more symbolic possibilities, allowing her characters to become figures for heroism, fate, and freedom. The trilogy offers a resonant and folkloric depiction of personal confrontations the war brings to light, as though, as with the war at Troy, the Civil War makes everyone heroic, no matter how flawed they might be.

That the situations in these three plays only obliquely invoke the body politic testifies to Parks’ canny sense of how to keep matters in scale. The stories she tells us are about determining one’s self-worth, and for the key figures here—Hero (James Udom), his lover Penny (Eboni Flowers), and possible rival Homer (Julian Elijah Martinez)—that struggle is bound by social restrictions, with slavery, like racism more generally, acting as a critical affront to liberty. But within those bounds there is also the question of one’s place in the cosmos and one’s place in one’s own skin, and Parks makes her characters equal to the question of what kinds of freedom there are—anywhere, at any time.

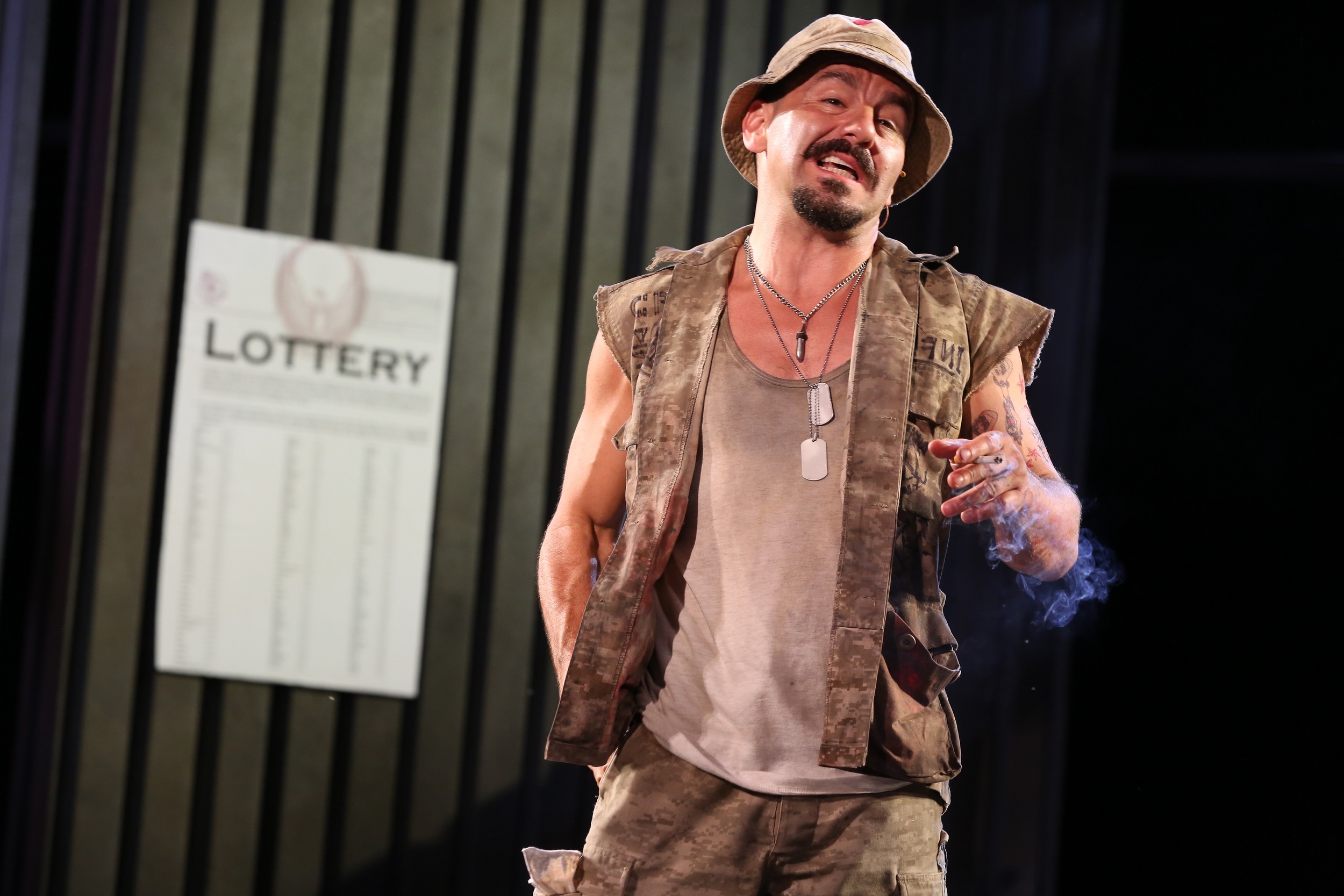

Hero (James Udom)

In the first play, “A Measure of a Man,” Hero wars within himself about whether to stay and work the field among the other slaves, or to ride into battle for the Confederacy with his “Master-Boss-Master,” the Colonel (Dan Hiatt), who has promised him his freedom if he serves and survives. On the one hand, there is Penny, who wants Hero to stay, and on the other, The Oldest Old Man (Steven Anthony Jones), Hero’s adoptive father, who fluctuates but sees the value of going to war. Homer, who we might assume to be a detached onlooker like his namesake the blind Greek bard, provides a third consideration. He has some crucial history with Hero, and that adds an element of possible expiation to Hero’s decision. An entertaining chorus of field-hands (Chivas Michael, Rotimi Agbabiaka, Safiya Fredericks, Erron Crawford) debates and takes bets on Hero’s ultimate decision; there’s also a singer with a guitar (Martin Luther McCoy) who frames the action. Hero, played with a worried thoughtfulness by James Udom, emerges as a heroic figure who takes upon himself the contention that freedom can be earned.

Smith (Tom Pecinka), the Colonel (Dan Hiatt)

In Part 2, “A Battle in the Wilderness,” there are three characters: the Colonel, who likes to sing little ditties about coming out on top, Hero, still servile, but now, near the war, more clearly equal or even superior to the old white man when it comes to survival, and Smith (Tom Pecinka), a wounded Union captain (allegedly) who, bleeding and encaged, is lower than Hero in this hierarchy. The struggle here is again for Hero’s soul, as we wait to see who he will side with—his “boss-master” whose side he is supposedly on, as a Southerner, or the Northerner, who is an “enemy” captive, and a stranger. In terms of racial difference, the Colonel has one of the most telling pair of speeches in the play, at first imagining his mourning when Hero, freed, leaves him, and then asserting his certainty that, no matter how bad things get, he can thank God he’s white. Later, the story of the Colonel’s fall will be played for comic effect, though its consequences are serious enough to Hero.

Odyssey Dog (Gregory Wallace), Hero/Ulysses (James Udom), Penny (Eboni Flowers)

In Part 3, the potential rivalry between Homer and Hero—returned from the war, having taken the name Ulysses—over Penny takes us into more straight-forward domestic territory, while a group of runaway slaves hang about as a new chorus, waiting “to jet.” There’s much more comedy here, provided by Hero’s garrulous dog, “Oddsee” (whose absence in Part 1 was seen as a bad omen), played with a nonchalant dignity by Gregory Wallace, particularly in a protracted exchange in which Penny and Homer wait on tenterhooks to hear the tale of Hero’s end. The resolution, such as it is, leaves us with Hero/Ulysses back where he started—but with a few key differences.

In each of the plays, Parks introduces what could be called a discordant note, and, in each case, its effect varies. In the first, it’s a story that comes to light about Hero and Homer, and the Colonel, in the past. The story undermines Hero, though we might also say it makes him more complex. In Part 2, the true nature of Smith makes that play’s triangulation even more emphatic, though perhaps too determined. And in Part 3, when Hero/Ulysses pulls a new fact from his pocket, we might question the merits of what seems a plot device more than a character flaw.

The Oldest Old Man (Steven Anthony Jones) and the cast of Part 1

There aren’t any flaws in Liz Diamond’s handsome and sure-footed production. The set by Riccardo Hernandez is starkly simple but effective, with iron girders in the place of trees and an open playing space that Yi Zhao’s lighting makes dramatic use of, in particular the silhouettes in Part 1. The showmanship of Martin Luther McCoy is a great asset to the production, and Gregory Wallace as Hero’s dog pretty much steals the show in Part 3.

Penny (Eboni Flowers), Odyssey Dog (Gregory Wallace), Leader (Chivas Michael, seated), Second (Rotimi Agbabiaka), Third (Safiya Fredericks), Homer (Julian Elijah Martinez)

Udom shows us how Hero’s vacillations and justifications mark his struggle. Hero’s sense of his servitude to the Colonel as in some key way defining offers us a sense of how personal worth can be tied to accepting one’s fate. Freedom can be a shock to such certainties. As Penny, Eboni Flowers commands sympathy without tipping into anachronistic attitudes toward her role in the triangle. As Homer, Julian Elijah Martinez gives a nicely understated performance, creating a knowing tone for an enigmatic character. The moodiness of Dan Hiatt’s Colonel helps to make Part Two dramatically compelling, aided by Tom Pecinka’s finely nuanced take on Smith, a role that could be called more a device than a character.

Hero (James Udom), Smith (Tom Pecinka)

Epic and almost impossibly ambitious in concept, Suzan-Lori Parks’ defining trilogy receives a masterful production at the Yale Repertory Theatre through April 7, then moves to San Francisco's American Conservatory Theater from April 25 to May 20.

Father Comes Home from the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3

By Suzan-Lori Parks

Directed by Liz Diamond

With songs and additional music by Suzan-Lori Parks

Choreography: Randy Duncan; Scenic Design: Riccardo Hernández; Costume Design: Sarah Nietfeld; Lighting Design: Yi Zhao; Sound Design and Musical Direction: Frederick Kennedy; Production Dramaturgs: Catherine María Rodríguez, Catherine Sheehy; Technical Director: Latiana (LT) Gourzong; Vocal and Dialect Coach: Chantal Jean-Pierre; Fight Director: Rick Sordelet; Wig Designer: Cookie Jordan; Stage Manager: Shelby North

Cast: Rotimi Agbabiaka, Erron Crawford, Eboni Flowers, Safiya Fredericks, Dan Hiatt, Steven Anthony Jones, Julian Elijah Martinez, Martin Luther McCoy, Chivas Michael, Tom Pecinka, James Udom, Gregory Wallace

Yale Repertory Theatre

March 16-April 7, 2018