Late in Shakespeare’s Tempest, Prospero, having dazzled Ferdinand, his daughter’s suitor, with a phantasmal pageant in which goddesses bless the couple’s imminent nuptials, insists that the spectacle was transitory as life itself and, the lines strongly suggest, as is theater, which all-too quickly “melts into air, into thin air.” But soft! All’s not lost. For look you: The Yale Summer Cabaret Shakespeare Festival has not yet wrung down the curtain and joined the choir invisible. There are two weeks yet—18 performances—in which to catch-as-catch-can the miraculous transformations of the basement space at 217 Park Street into Prospero’s isle, and into the Forest of Arden, and into a contentious arena for the bloody feuds of Britain’s royalty (yes, that’s three different sets and sometimes two shows a day—can ambition be made of sterner stuff?).

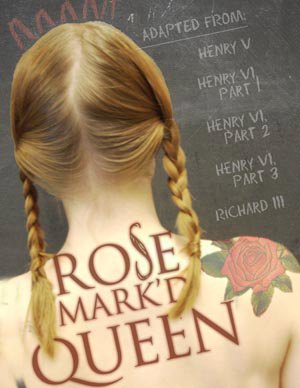

The three shows are The Tempest, As You Like It, and a right witty concentration of Henry V, Henry VI, Parts 1, 2, 3, and Richard III into a blood-and-guts psycho drama called Rose Mark’d Queen. And the shows boast a concentrated cast that have been playing their parts all summer, becoming one with their characters’ antic dispositions, their sighs and fleers and jests, their studied mummery, festive songs, passionate proclamations, yea, their wanton romps, clownish conceits, and vaulting ambitions. And before each production there is most excellent meat in the form of short presentations, much to the point, on aspects of Shakespearean theater: on sets, pre-The Tempest; on the language, pre-As You Like It; on the use and abuse of history, pre-Rose Mark’d Queen.

Having seen all three shows twice, at opening and at a little past mid-point, I can observe that the vision of Shakespeare on view at the Cab is of malleable texts in service to the joys of playing. While respectful of the poetry of the plays, these productions are not servile flatterers of the Bard’s big rep nor timid courters of the audience’s clemency. Each show grabs for what it wants to wrest from the play, and each has the guts and gusto and gonads to make it work, mostly.

The Tempest (directed by Jack Tamburri) is largely played for laughs, suborning its romance elements and the tensions about legitimate and illegitimate power to a broader conception of general folly. The part of Prospero is shared among the company and this adds a lively sense of make believe to the entire proceedings. Off-putting, perhaps, if you’d rather have some fledgling McKellan imposing his magic on the hapless visitors to his island kingdom, but, as the play rolls along, the odd overlaps as each actor takes turns with the cloak and book begin to wield a life of their own. As a device it’s nimble enough to invite reflections on who lords it over whom—even Miranda and Caliban get to “be” Prospero at times—and as theater it’s a challenge to our efforts to “enter into” the play, though a form of “magic” in its own right. Some highpoints for me: the comic timing of the cast in the mutterings of the stranded aristocracy—King Alonso, his brother Sebastian, Duke Antonio, and Gonzalo (it’s rare to want to spend more time with these characters)—and Ariel’s songs as voiced by Adina Verson, in a get-up that put me in mind of a Dr. Seuss creation.

As You Like It (directed by Louisa Proske) presents a likeably fast-paced first act outside in the courtyard, complete with a wrestling contest and some agreeable love-at-first sight importunings between Adina Verson’s breathless Rosalind and Marcus Henderson’s open-book Orlando. Inside, things get mellow with a sojourn in the forest of Arden that’s perhaps a bit too long on songs. The cast plays and sings right well, but one begins to realize that the best parts of the play happen when Rosalind’s on stage, for its her native intelligence and wit, her skill at directing and counterfeiting (like The Beatles’ song says: “and though she feels as if she’s in a play, she is anyway”), and her experience of all roles (pined for and pining after, male and female, fool and critic) that create the intellectual content of the play. This production aims for and mostly achieves a feel for touching comedy spiced with the absurd spirit of contemporary Rom-Coms. Highpoints: Rosalind’s dialogues with her confidante Celia/Aliena and her repartee with Orlando; the brothers Duke, both given a comic kick-in-the-pants by Brenda Meaney in wildly different tonsorial and sartorial style; Babak Tafti as the put-upon fool Touchstone burdened with his Lady’s luggage, and in his lust-above-love courtship of game Audrey (Jillian Taylor); Tim Brown’s lovesick swain and Tara Kayton’s fiery Phebe; Matt Biagini’s mercurial satire of melancholic Jaques.

Rose Mark’d Queen (directed by Devin Brain) serves up a fast-paced interpretation of a handful of Shakespeare’s histories, centered by strong characters—King Henry VI (Marcus Henderson, gaining in pathos and stature as the play proceeds) and his Queen Margaret (Jillian Taylor in a demanding role in which she is lover, chider, schemer, fiend and grief-stricken mother by turns)—with more than able support provided by Babak Tafti, as several figures in the House of York, providing now fierce, now more bemused opposition to the King and his supporters, Matt Biagini in a number of supporting roles pretty much destined for death, and Andrew Kelsey, who shines bright as Suffolk, the Queen’s power-hungry lover, and then, as Richard, becomes a lethal attack dog off the leash. The first half is razor sharp, moving from a scene of kids playacting battle and martial pomp to acts of murderous treason; the second half dallies a bit more, with a comic courtship scene (of an inflated doll) presumably to lighten things up though it also seems to lengthen the proceedings more than is needful. High-points: when a sword is held at the throat of an audience member to force a capitulation; when representatives of York and Lancaster go amongst the audience, trying to enlist supporters by drawing upon them either a white or red mark (even your selection of a wine for the evening might be a political gesture!—stick with beer and support Jack Cade); the use of light and sound and those big armoires at either end of the space. It’s a play that keeps you guessing and, of the three, was the one that impressed me most, if only because Brain has somehow managed to underscore how these histories are proto-versions of many more familiar moments in Shakespearean tragedy.

What’s gratifying, for a returning spectator, is to watch the audience get caught up in the pressures of the plays, waiting to see the knots come undone—two of the plays do end happily—and to marvel at how inviting and interactive Shakespeare can be. These aren’t pious productions stuffed with pretty pomp set up on a stage leagues away. This is an in-your-face—maybe even on-your-lap—Festival, with characters beseeching their audience to take a side, share a dilemma, lend an ear. If you think you know the plays, I guarantee you you don’t quite know them like you’ll find them here.

And that’s all to the good. For what are plays anyway? Certainly they are texts, but if you want a scholarly Shakespeare, stay at home and read a book. If you want to hear Shakespeare alive and lived, given shape by young talent and shared as though a communal feast, then stay not, unresolved, unpregnant of your cause (to go or not to go) but exeunt omnes and severally and head for the Yale Summer Cabaret’s Shakespeare Festival.

The Yale Summer Cabaret Shakespeare Festival August 2-14 Artistic Director, Devin Brain; Producer, Tara Kayton

203-432-1567; or summercabaret.org

“Art” by Yasmina Reza first appeared in Paris in 1995. Shortly afterwards it was translated into English for the British stage and turned up at the Royale Theatre (now the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre) on Broadway on March 1, 1998. The cast was stellar for this three-person play, performed without intermission. The six-month Broadway run included Alan Alda, Victor Garber, and Alfred Molina, all well known film and theatre performers.

“Art” by Yasmina Reza first appeared in Paris in 1995. Shortly afterwards it was translated into English for the British stage and turned up at the Royale Theatre (now the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre) on Broadway on March 1, 1998. The cast was stellar for this three-person play, performed without intermission. The six-month Broadway run included Alan Alda, Victor Garber, and Alfred Molina, all well known film and theatre performers.