The Yale Cabaret’s Season 44 ended last month and a number of its practitioners will be graduating from the Yale School of Drama this month. The work the YSD students do at the Cab doesn’t count as part of their work toward graduation—it’s done for love of theater and for the joy of working together on pet projects. And for numerous Cab fans, the productions at the Cab—intimate, avant-garde, inspired, off-the-wall, experimental, outrageous, inviting—are the live wire of the YSD season. And so it’s time for a “thanks for the memories” moment to take note of the more memorable productions, performances, and displays of artistry that took place in the 2011-12 season (the procedure here: four notables in each category, chronologically by production date, with the fifth-mentioned earning top billing, in my estimation) [note: dates after names indicate prospective year of graduation from YSD]:

First, overall Production: the skilled staging of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, produced by Michael Bateman (*13); the comically outrageous first-semester ender, Wallace Shawn’s A Thought in Three Parts, produced by Kate Ivins; the frenetic staging of Adrienne Kennedy’s The Funnyhouse of a Negro, produced by Alyssa Simmons (*14); the moody, musical trip to the underworld, Basement Hades, produced by Kate Ivins; and . . . the crowd-pleasing Victorian Gothic Camp of Mac Wellman’s Dracula, produced by Xaq Webb (*14).

Next comes attention to the technical accomplishments that are often so remarkable in transforming the tiny, unprepossessing space of the Cabaret:

In Set Design: Kristen Robinson (*13) for creating the distinct spaces of Persona; Adam Rigg (*13) and Kate Noll (*14) (aka Daniel Alderman and Olivia Higdon) for the gallery exhibit space of Rey Planta; Reid Thompson (*14) for the creepy and campy locations of Dracula; Brian Dudkiewicz (*14) for the historical and ethnic space of The Yiddish King Lear; and . . . Kate Noll (*14) for the Miss Havisham-like clutter of The Funnyhouse of a Negro.

For work in Costumes: Martin Schnellinger (*13), for the interplay of clothed and unclothed in A Thought in Three Parts; Elivia Bovenzi (*14), for helping create the theatrical layers of The Yiddish King Lear; Kristin Fiebig (*12), for the fantasia of whiteness in The Funnyhouse of a Negro; Nikki Delhomme (*13), for the lively get-ups of Carnival/Invisible; and . . . Seth Bodie (*14), for the uncanny outfitting in Dracula.

For memorable work in Sound Design: Palmer Heffernan (*13), for the roving speakers in Street Scenes; Ken Goodwin (*12), for the atmospheric aura of reWilding; Jacob Riley (*12), for the full scale presence of Dracula; Palmer Heffernan (*13) and Keri Klick (*13) for the soundscape of Basement Hades; and . . . Ken Goodwin (*12), for the wrenching sound effects of The Funnyhouse of a Negro.

For illuminating work in Lighting: Solomon Weisbard (*13), for the psychic landscapes of reWilding; Solomon Weisbard (*13), for the interplay of lights with movement in Clutch Yr Amplified Heart and Pretend; Masha Tsimring (*13), for the moody madhouse of The Funnyhouse of a Negro; Masha Tsimring (*13) and Yi Zhao (*12), for the Underworld of Basement Hades; and . . . Masha Tsimring (*13), for the stylish thrills of Dracula.

For striking use of Visuals: Paul Lieber (*13)’s projections and “home movies” in Persona; Christopher Ash (*14, aka Glenn Isaacs)’s ghostly projections in Rey Planta; Michael Bergman (*14)’s intimate use of visuals in Creation 2011; Michael Bergman (*14)’s atmospheric projections in Dracula; and . . . the rich use of projections in Basement Hades, by Hannah Wasileski (*13), and assistants Michael Bergman (*14), Nick Hussong (*14), and Paul Lieber (*13).

For striking use of Music: the ambiance of Sunder Ganglani (*12) and Ben Sharony’s music-scapes in Slaves; the mood-setting popular songs in Persona; the expressive tunes in Clutch Yr Amplified Heart and Pretend; the accompaniment and sound effects of The Yiddish King Lear, Dana Astman, Music Director; and . . . the beautifully evocative score and performances of Basement Hades, Daniel Schlosberg, Composer, and Schlosberg and company as the instrumentalist Orpheuses.

One of the strengths of the Cabaret is its mix of pre-existing plays with new, often conceptual creations by students in YSD or in other disciplines at Yale. First, among the published plays offered, the ones I was most pleased to make the acquaintance of: Persona, Ingmar Bergman’s harrowing exploration of the self; Rey Planta (translated by Alexandra Ripp, *13), Manuela Infante’s caustic exploration of manic consciousness; Dracula, Mac Wellman’s comic exploration of vampirism and Victorian mores; The Funnyhouse of a Negro, Adrienne Kennedy’s haunting exploration of racial identity; and . . . Church, Young Jean Lee’s arch and affecting exploration of religious community.

Among the concept pieces this year—and Season 44 was strong in such offerings—the ones I liked best were: Slaves, an enigmatic investigation of theater by Sunder Ganglani (*12) and the ensemble; Creation 2011, a celebration of awkward theatricality by Sarah Krasnow (*14) and the ensemble; Clutch Yr Amplified Heart and Pretend, a celebration of theatrical movement by the ensemble; Carnivale/Invisible, a questioning of American entertainment by Ben Fainstein (*13) and the ensemble; and . . . the deft interweaving of myth and music in Justin A. Taylor (*13) and the ensemble’s Basement Hades.

And, because most of the shows at the Cab feature strong ensemble work, let’s recognize special merit in ensemble: the entire lubricious cast of A Thought in Three Parts; the large cast of seekers in reWilding; the mad women at the table, and their attendants, in Chamber Music; the actors in the play, in the Purim play within the play, and in the audience in The Yiddish King Lear; and . . . the demonically entertaining cast of Dracula.

With so much concept and ensemble work, it becomes trickier to pick out individual performances, but I’ll follow the industry practice of dividing performances by gender and proceeding as if these actors/actresses can somehow be subtracted from the wholes of which they provided memorable parts, ladies first:

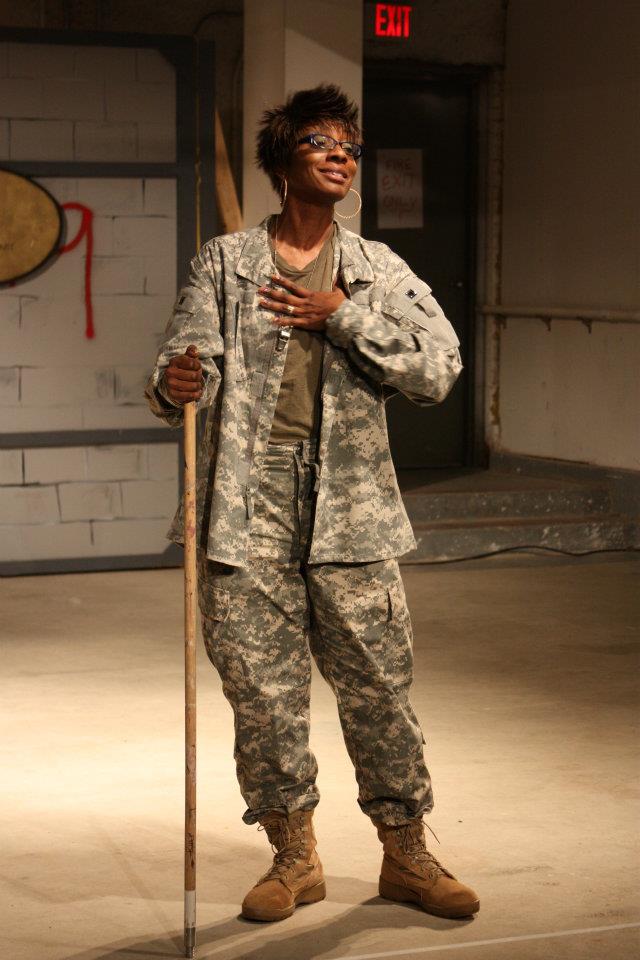

For her expressive, uninhibited performances in Slaves, A Thought in Three Parts, and Clutch Yr Amplified Heart and Pretend, Jillian Taylor (*12); for her roles as the silent actress in Persona, the voice in Rey Planta, and the stridently “sane” Amelia Earhart in Chamber Music, Monique Bernadette Barbee (*13); for her riveting portrayal of the conflicted nurse in Persona, Laura Gragtmans (*12); for her awkward Joan of Arc in Chamber Music, and her deliciously demur and brazen Lucy in Dracula, Marissa Neitling (*13); and . . . for the stand-out performance of Season 44: Miriam Hyman (*12) in The Funnyhouse of a Negro.

For his roles as the blinking, speechless king in Rey Planta, and as the badgering inspector in Christie in Love, Robert Grant (*13); for his intensely realistic character studies in reWilding, Dan O’Brien (*14); for his scene-stealing Van Helsing in Dracula, Brian Wiles (*12); for his kvetching patriarch in The Yiddish King Lear, William DeMeritt (*12); and . . . for his play-as-cast gusto in such roles as the confused husband in Persona, the appalled constable in Christie in Love, the babbling, spider-eating Jonathan Harker in Dracula, and the unforgettable Chicken Man in reWilding, Lucas Dixon (*12)

And for great work in directing: Alex Mihail (*12), for exploring the psychic tensions of Persona; Dustin Wills (*14), for orchestrating the varied misfits in reWilding; Jack Tamburri (*13), for finding the perfect pitch for the vaudevillian creepshow of Dracula; Ethan Heard (*13), for conducting the interplay of music, miming, and monologue in Basement Hades; and . . . Lileana Blain-Cruz (*12), for the inspired tour de force mania of The Funnyhouse of a Negro.

Deep appreciation for all the work and all the fun, and . . . see you next year!