Review of Spring Sonnets by Don Yorty

In his sonnets, the poet Don Yorty gives us a piece of his mind and a chunk of his spirit.

Not so much small as compact, that literary miniature known as the sonnet has held pride of place—not just in English—for 500 years. From the oft-quoted creations of Shakespeare and John Donne to Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets, 1964—considered his greatest work—the 14-line stanza, of varying rhyme schemes and assorted structures, has proven a satisfying form. Is it the brevity? Is it the fact that, whether as writer or reader, we know approximately what we’re getting? Is it because this deft instrument seems particularly amenable to certain feeling-states, or to any?

To one writer it’s a nature poem, to another the perfect vehicle for elegy or celebration. For the late Wanda Coleman in her American Sonnets, it’s a vehicle for ex-lover vengeance, bitter wit, and funky reminiscence. This malleability provides a good deal of the sonnet’s allure. You can cover the waterfront of feeling and experience. The poems may look similar but produce all manner of effects.

In the paragraph-length afterword to his Spring Sonnets, New York poet and novelist Don Yorty says he began writing sonnets after not having written a poem for twenty years. The immediate occasion, he explains, was America’s invasion of Iraq in 2003. “I think because I opposed the invasion so much,” he writes, “I needed something I could control.” The sonnet was something he’d never attempted. He wrote 180, initially, then culled them to the 90 included here.

Bush’s criminal war may have been the catalyst, but the war and its destruction and the more general predations of imperial policy are rarely mentioned in Spring Sonnets. Rather, war as a constant presence constitutes the psychological and spiritual backdrop to Yorty’s poems, creating a sense of helplessness and existential angst that is our “new normal,” out of which a new awareness, a clearer vision, comes into being and is duly recorded (think Auden in the Thirties). Poem #20 is one of the few that mentions the war(s). Here it is in full:

Just as I write two hawks above the trees

fly fast away. Shadow of a buzzard

passes over my shoulder hopefully.

I was expecting rain, impeded start

but the sun’s come out, made the day open

as a pursued lover turning might smile

and kiss me on the mouth. Surprised I am

chosen I am happy as can be while

everything gets worse. Soldiers still fight

in Afghanistan and Iraq, two wars

I hadn’t wanted, but then who am I?

The wind blows my pages while I write for

those killed in battle. Wind, give me the breath

the word eternal not alive or dead.

The tone, typical throughout this volume, is both personal and direct. The method lets the poet trace out the movement of thought across the mind, notating the places where it happens to land. Anything is game, and any set of circumstances, seemingly, can make this happen. For instance, thought itself becomes subject to examination, as in #28 where Yorty pauses to reflect on language and its relation to consciousness and cognition:

[…] What’s thinking

but flying, following thoughts. Why are they

always words?

They’re not, of course. Thoughts are often simply feelings to which specific sounds have yet to attach. Or, if they are attached, are not words. (Music, for instance, where tonality leads us directly into specific, but undefined, emotional states.) This is an idea that quickly gathers complexity. The poet’s question is rhetorical, necessarily, since to answer it would take us into linguistics and theories of language. Yorty’s sonnet, whether considering the relation of thought to words or of a private citizen to war, is allusive rather than exploratory. Its insights awaken curiosity rather than supply answers.

The poems are intimate, not so much in the “confessional” way wherein contemporary American poetry makes the Catholic church look like a piker, but in the sense of their tone being wholly unguarded. If making decisions, or forming clearer observations, arrives as a result of the various voices in our heads engaging in debate, then on these pages we’re allowed (encouraged?) to eavesdrop. This tone of confident disclosure makes for an engaging and ongoing I-and-thou effect. Reading these puts us in the presence of a mind often astonished at the ordinary because the ordinary rarely is merely that to a mind willing to look further or deeper, or to step back and gain perspective about what it observes. This curiosity and commitment enable the poet to take on just about any subject matter and say something startling or new.

Yorty does not abuse that freedom by running hither and yon, making us chase after his meaning. He sticks to his ken, and that adds to the power of the performance. Spring Sonnets maps out a world the reader can readily comprehend and stays there. That world consists of two places: the New York City neighborhood where Yorty has lived and worked as a second-language instructor for thirty years, and a rural retreat somewhere in the Pennsylvania mountains. The poems move between these locales. A single season is the time frame, what happened then is the subject matter.

More importantly, the poetic voice leans on experience without making that the point, giving the poems not just a significant tonal difference but determining choices all around: what to notice, what to write about, what to say, finally. The first sentence of Sonnet #31, for instance (“Today for the first time in my life…”) launches a disquisition on technology. The loss of a cell phone becomes a reverie about the telephone. No one ever lost one when it came with a cord plugged into a wall. Moreover, there was a time when if you noticed someone walking down the street alone and talking volubly, the implication was that mental illness was somehow involved. Now we see such behavior all the time and assume a cell phone conversation is taking place. But our reliance on this torqued up communication device means “no one’s alone anymore.” The fact that technology shears away, one by one, the dimensions of privacy, is alarming but inescapable.

[…] Times change. There’s nothing about

it you can do, if you don’t change, you

don’t move and you’re run down by the future.

Whether it’s Cachito the cat, squirrels on a park bench, a butterfly making its way across a pond, whatever the subject these poems are invariably meditations on the immediate, as for instance #41 (“At any moment it’s going to rain…”), wherein a rainstorm effectively stops composition in mid-measure. Add to that the notion that anything is a fit subject for poetry and (thank you, Dr. Williams) what results is a simplicity of expression and gratifying absence of self-conscious literary affect. In poems mentioning war, politics, death, classroom repartee, or describing the woods or milkweed pods, the effectiveness of the level of engagement owes much to the plain-speaking that avoids that recognizably elevated vernacular—poetry!—alerting readers that someone’s trying to say something important. The voice of Spring Sonnets is the same one we use to share our thoughts and observations in everyday conversation. Sonnet #19 (“My hands are numb and yet the sun is bright.”), for instance, observes and records the changes evident in nature as spring manifests. Its subject is the strange, unfolding chaos that ensues when the temperature rises a few degrees and the grip of frost is broken. It’s the suddenness and multifariousness of this process that always surprises, and that effect is replicated in certain details (bird sounds, vanished ice, sudden appearance of white flowers) before shifting to thoughts of how we change as we get older, looking behind to that time of life—youth—when we tended to think only of ourselves.

Though sonnets can be about anything, they gained their preeminent place in English as expressions of love. Love is not just ardor, romance or sexual attraction. The Greeks, for instance, recognized multiple forms of love, including affection, friendship, familial love, universal love (for strangers, nature, or God, known as Agape), practical love and self-love. All emerge in these poems one way or another. The transforming power of love is Yorty’s theme here, I suspect, because, as an older poet “with time to spare but not one hour to waste,” he sees love as an animating force, always present, often concealed:

[…] As I grow

old it seems possible to really love

even the startled snake scared in the leaves […]

That’s not to say the view is all Woodstock. When the poems shift back from the Poconos to the Lower East Side, a certain tension surfaces. Poem #11, for example, fumes at the manner in which a crew of anarchists trashed the local public space, “gerrymandered the park bench to drink, drug / take a long piss when the beer filled them up.” The poet’s willingness to go where emotion takes him—whether pleasant, deep or seriously annoyed—deepens the tone of Spring Sonnets. Mostly, though, Yorty takes the long view, one in which light stands in for our fleeting present and night is the death that’s waiting around the corner.

This being a book of sonnets, it’d be impossible not to weigh in on technical matters. Various rules hold that, for instance, the lines of a sonnet must be ten syllables each, that sonnets are written in iambic pentameter, that they deploy end rhymes in an ABAB CDCD pattern, etc. All that would’ve made for a different kind of book than Spring Sonnets. Here the rhymes, internal and at line ends, are playful rather than constricting or self-conscious. Some, like the poem that got rained out, employ ABBA end rhymes, some AABB. Slant rhymes often suffice and are gestural, even whimsical. Several times, for example, the poet rhymes “a” with “the.” This works both to keep the lines rolling and to acknowledge the five-century provenance of the form. The sonnet, here, turns out to be the mode most appropriate for Don Yorty’s re-entry as a poet. He’s clearly comfortable working it and it works because he knows how to make it work. As Sonnet #158 notes: “…the music’s always true while it plays.”

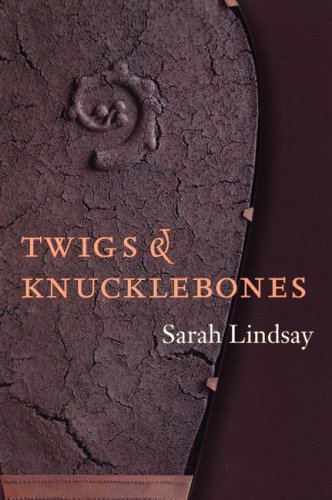

Spring Sonnets

By Don Yorty

Indolent Books, 2019

Paperback, 114 pages

The book may be ordered here.

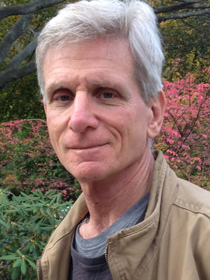

Don Yorty is a poet, educator, and garden activist living in New York City. He is the author of two previous poetry collections, A Few Swimmers Appear and Poet Laundromat (both from Philadelphia Eye & Ear), and he is included in Out of This World, An Anthology of the Poetry of the St. Mark’s Poetry Project, 1966–1991. His novel What Night Forgets was published by Herodias Press in 2000. He blogs at donyorty.com: an archive of current art, his own writing, and work of other poets.

Jim Cory’s most recent publications are Wipers Float In The Neck Of The Reservoir (The Moron Channel, 2018) and 25 Short Poems (Moonstone Press, 2016). He has edited poetry selections by contemporary American poets including James Broughton (Packing Up for Paradise, Black Sparrow Press, 1998), Jonathan Williams (Jubilant Thicket, Copper Canyon Press, 2005), and, most recently, Have You Seen This Man, the Castro Poems of Karl Tierney (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2019).