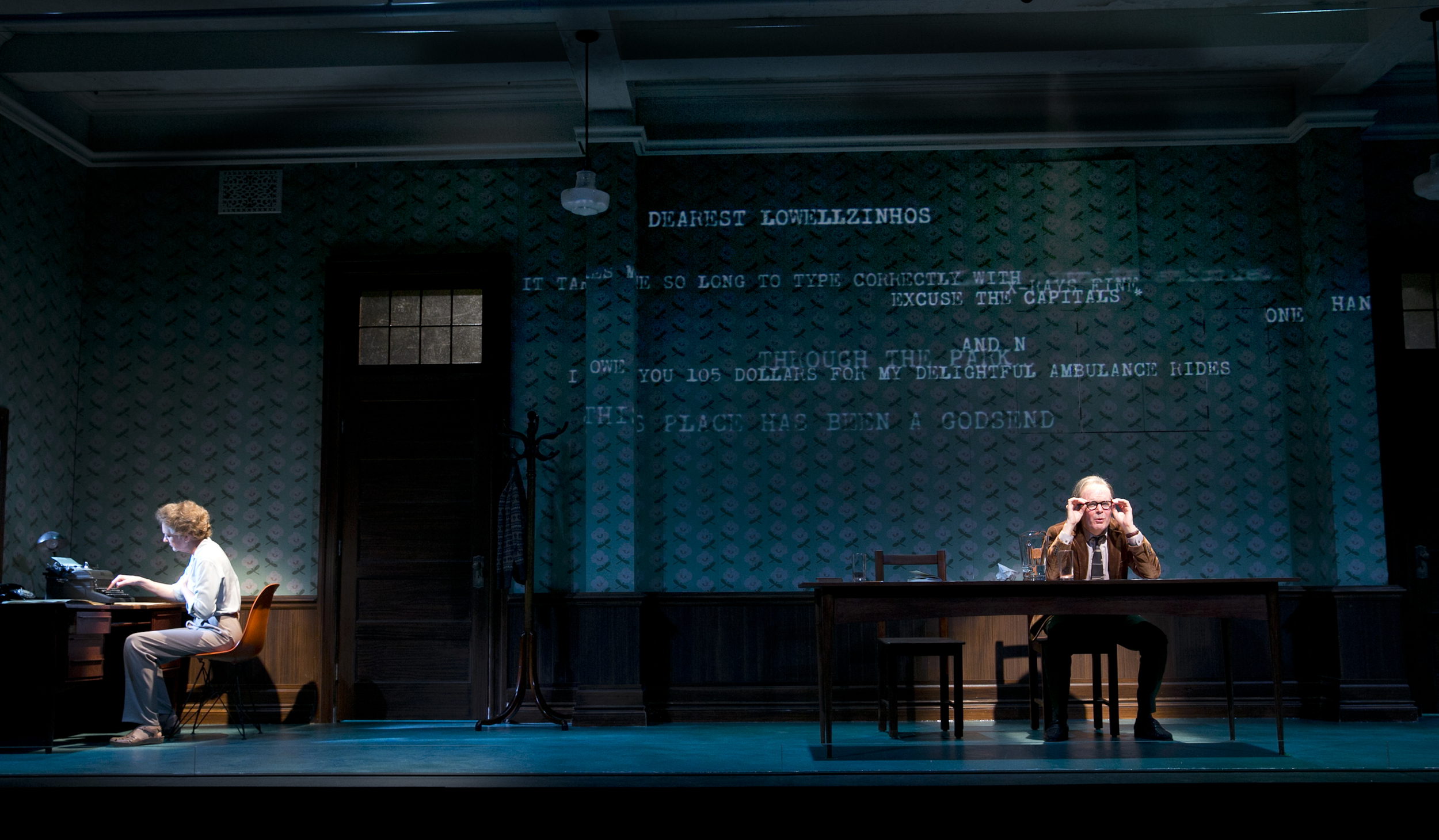

Rarely does Broadway come to York Street, but Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Sunday in the Park with George, the thesis show from YSD directing student Ethan Heard, brings to the University Theater a sense of the “big production.” Heard’s approach, with Scenic Designer Reid Thompson, makes the most of the huge stage space at the UT, letting props rise and fall, letting the wings remain visible throughout, setting the orchestra at the back of the stage, using a raised, tilted platform as “la grande jatte”—the setting for French painter Georges Seurat’s neo-impressionist masterpiece—and staging the scenes in George’s studio at the footlights. Not only does Heard’s production use stage space in all its variety, it uses painterly space in interesting ways: there are empty canvas frames to let us see George (Mitchell Winter) at work, and hanging sketches to show us what he’s so busily working on. When one of the sketches explodes into color thanks to some wonderful work with projections (Nicholas Hussong), the visual panache of the show ratchets up a notch. All in all, the show is a spectacular, from the care with which the costumes (Hunter Kaczorowski) match the figures in Seurat’s painting, to the use of compositional space in arranging the figures, to the effects of color and light (Oliver Watson, Lighting Design) able to suggest the Neo-Impressionist’s approach, to—in Act Two, set in the Eighties—hanging TVs and subtly illuminated canvases, to say nothing of one helluva blue suit.

In the cast, the star of the show is Monique Bernadette Barbee as George’s girlfriend and reluctant model, Dot, and, in Act Two, as Marie, Dot’s daughter who claims George as her father. Barbee seems simply born to be on a stage, able to find Dot’s roguish nature, her plaintive bid to be George’s main love—she loses out to painting—and her strength in “moving on.” As Marie, Barbee's delivery of “Children and Art,” hunched in a wheel-chair, is the most affecting segment of Act Two, and her bravura opening song of Act One, “Sunday in the Park with George” is, frankly, a hard act to follow. The play starts off with its best bit, in other words, and we have to wait awhile before anything as enthralling takes place again.

Along the way, there’s fun with two culture vultures, Jules (Max Roll) and Yvonne (Ashton Heyl), in “No Life,” movement and mood from the entire company in “Gossip” and “Day Off”—Robert Grant handles the physicality of Boatman well, and Marissa Neitling and Mariko Nakasone are chipper and silly as Celeste 1 and Celeste 2—and “Beautiful,” a thoughtful song delivered in a sparkling vocal by a reminiscing Old Lady (Carmen Zilles). The professional and personal setbacks of George are paralleled to his increasing obsession with his method, and that’s enough to keep the wheels turning within a set that never stays still.

And Act One does deliver a great ending to match the great beginning: the entire Company—and all the tech assistance—is to be commended for making “Sunday” come together. It’s the sequence in which the pieces of George’s great canvas finally fall into place, and it’s one of those theatrical moments often referred to as a “triumph of the human spirit,” except here it’s actually the triumph of artistic method. Sunday on the Isle of La Grand Jatte is the painting that showed the full artistic possibilities of Seurat’s method, generally called “pointillism” (after the French word “point” or “dot”), and seeing the composition come together, as George, singing his mantra, moves the quarrelsome and busy-body characters into their defining places, in a burst of color and with the best melody in the play, gives one of those curtains that theater is all about.

The problem is that Sunday in the Park with George has little to offer by way of an Act Two. Perhaps, in the Eighties, when the play debuted, seeing the Eighties artworld put on stage had a freshly satirical edge, but from our standpoint now, it’s just an excuse to dress up the characters in clothes of yet another “period” (I particularly liked the costumes for George (Winter, as Seurat’s alleged great-grandson), Naomi Elsen (Ashton Heyl, as a stagey video artist), Blair Daniels (Carmen Zilles, as a brittle art critic) Billy Webster (Matt McCollum, in quintessential art connoisseur duds), and Alex (Dan O’Brien, reeking of SoHo). Indeed, looking the part is pretty much being the part in Act Two, as there is even less in the way of characterization available for these actors. Again, it’s Barbee, as Marie and Dot, who gets the plum bits, and she delivers; Barbee's rascally Marie upstaging her grandson at his art expo makes her very much Dot's daughter.

As Act One George, Winter does intensity well, making us feel how driven and difficult George can be. His best song segment is the playful mocking of his models and patrons in the voice of two dogs in “Day Off,” and in duet with Barbee for the quite affecting number “We Do Not Belong Together,” a song that spells out the romantic chasm between the lovers. In Act Two, Winter and the Company put a lot of energy into “Putting It Together” but there’s something in his manner that makes this George not matter to us. Ostensibly, the point is to bring present-day George into line with previous century George, but there’s not much pay-off in that happening because there doesn’t seem to be much at stake.

As entertainment, the play’s comedy is a bit wan, having to do mostly with hypocritical French bourgeois and stupid American tourists (Matt McCollum and Carly Zien—we could’ve used more of them) of the 19th century, and preening, pretentious art-world aficionados of the 20th. Even with its clever opening song, “It’s Hot Up Here,” which matches the discomfort of actors forced to remain motionless with figures frozen on a canvas for all time, Act Two is mostly anti-climax.

The YSD production works as an ambitious staging of a bit of Broadway and its pleasures are not to be missed. Sondheim and Lapine are best at characterizing that sequence of Sundays in the park, and Heard and company are best at putting all the pieces together. As the song says, “There are worse things.”

Sunday in the Park with George Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by James Lapine Directed by Ethan Heard

Musical Director, Conductor, Orchestrator: Daniel Schlosberg; Scenic Designer: Reid Thompson; Costume Designer: Hunter Kaczorowski; Lighting Designer: Oliver Wason; Sound Designer: Keri Klick; Projection Designer: Nicholas Hussong; Production Dramaturg: Dana Tanner-Kennedy; Stage Manager: Hannah Sullivan

Yale School of Drama December 14-20, 2012

Photographs by T. Charles Erickson