There’s no doubt that Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell were two of the most gifted poets of their generation. And there’s no doubt that theirs was a long-lived relationship of, to some degree, kindred spirits. Nor is there any surprise in finding that their letters to each other are well worth reading—as glimpses into the working process, into the world of letters in the first exciting decades of post-World War II America, and into the always fraught and dramatic life that seemed de rigueur for any world-conquering poet of the day. And Dear Elizabeth, the play by Sarah Ruhl adapted from the letters of Bishop and Lowell, and directed by Les Waters, at the Yale Repertory Theatre, dispels any doubt that poets in their prose can make for compelling, moving and satisfying drama. Granted, it helps to be interested in the writing life, and, perhaps, in the relation of these two rare birds, but Dear Elizabeth’s greatest assets are characters who are articulate about their lives, and a time-scheme that roves through the thirty years—from 1947 to 1977—during which the poets corresponded, finding the highlights that make a relationship a story. The lifelong trade-off began shortly after they first met and continued until Lowell’s death—indeed, Bishop’s last letter to her friend was in the mail when she learned of his fatal heart attack at age 60 (Bishop, six years Lowell’s senior, outlived him by two years).

Creating theater out of the necessarily fragmented view of a relationship contained in letters is no small task, but it’s aided here by the considerable brio with which the letters were written, and by the fact that there was drama enough in the writers’ lives. During the period covered by the play, Lowell moved from first wife to second to third, and had children with the latter two; Bishop’s partner, architect Lota de Macedo Soares, with whom she began living in Brazil in 1951, committed suicide in 1967. And, from time to time, Lowell was placed under care for attacks of mania, while both poets had on-and-off affairs with the bottle. In Ruhl’s version, all interlocutors are left offstage; this is a two-person play illuminating how, for writers (and their readers) what they say to each other in writing is the measure of whatever happens in the mundane world where real lives are led.

Ruhl’s script carefully weaves bits of the correspondence into a love story of sorts. After years of collegial affection, Lowell (Jefferson Mays) seems ready to make things more intimate, perhaps even permanent—one of the most naked moments in the play is when Lowell looks back on an evening when it seemed possible to imagine Bishop and himself as husband and wife, stating that he nearly took the chance to propose but chose to wait for the right moment. Whatever she actually felt about such confessions, Bishop (Mary Beth Fisher) plays it close to the chest, neither repudiating her would-be lover nor giving him any encouragement. And yet, as played on stage, Fisher’s Bishop seems a woman who, initially, might be infatuated with Lowell enough to give him the impression he nearly acted on. At times, Bishop’s replies to Lowell, as he exults about fatherhood or advertises a new bride, seem brittle with envy if not jealousy.

Lowell, meanwhile, tends to brood, moving into so-called ‘confessional poetry’ as a means to make his life meaningful as art. The play gets some tension out of a terse and anxious exchange when Lowell, in his late poem “The Dolphin,” chooses to use excerpts—doctored to suit his purpose—from letters his ex-wife Elizabeth Hardwick wrote. The strength of Bishop’s condemnation of mixing “fact and fiction” spills over into what we might consider to be the sacred and private bond between correspondents—whether Lowell and Hardwick or Lowell and Bishop—so that Bishop, we might say, is seeing her own confidence violated in Lowell’s betrayal of Hardwick. Even more to the point, her harangue at Lowell might extend beyond his poem to Dear Elizabeth itself, where words never meant to be dramatized find themselves become a script. Whatever Bishop’s misgivings might be, we accept Ruhl’s intervention: public lives are always to some extent theatrical, and those who write must be ready to be re-written.

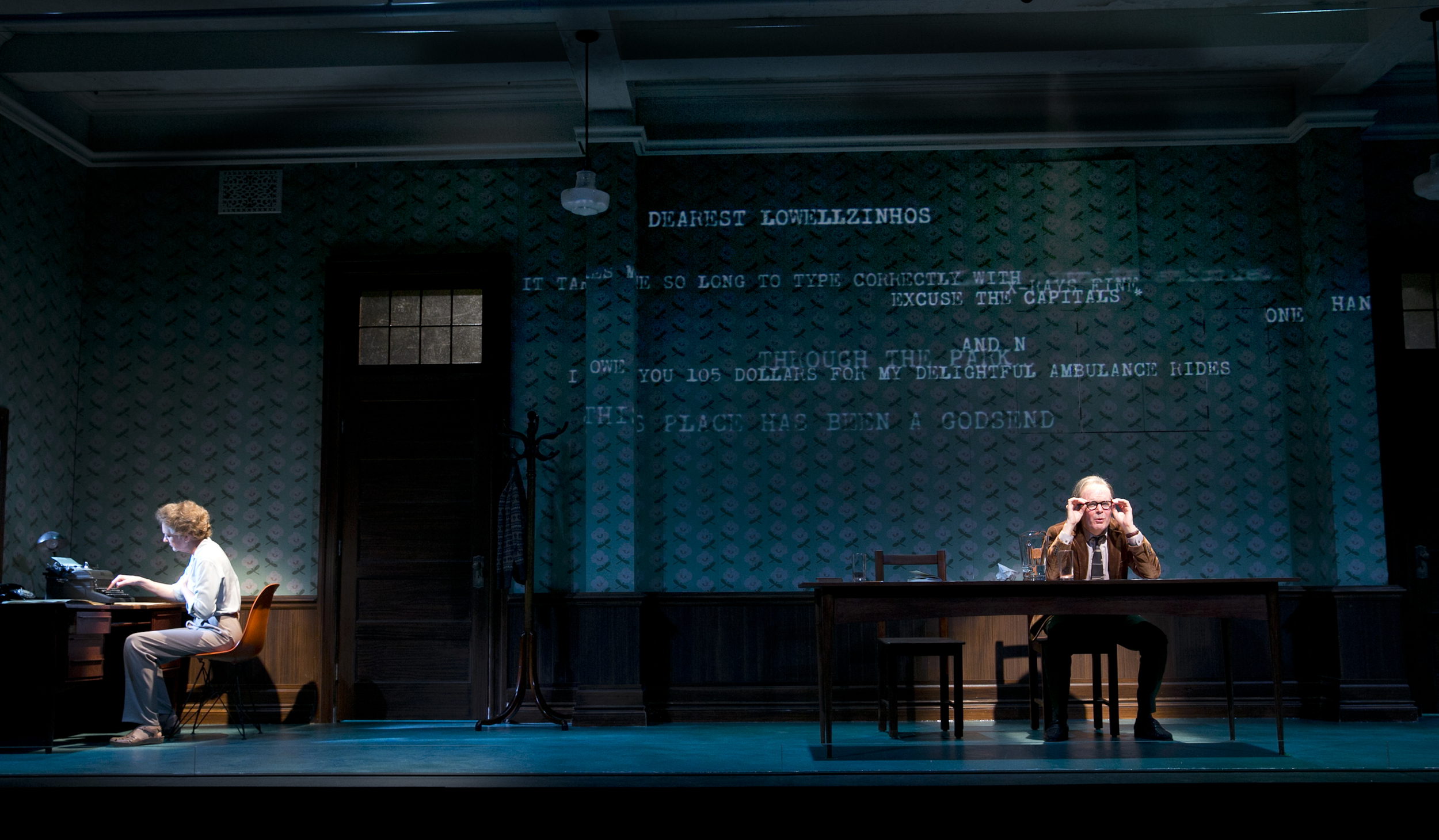

As theatrical experience, Dear Elizabeth uses scenic ingenuity to distract us from the fact that everything this play means is in the writing, in the fascinating signals, suggestions, confessions, comments, poem crits, and corrections that these two gifted persons choose to share with one another. Les Waters and Scenic Designer Adam Rigg have concocted some technical marvels—waters flood the stage at certain times, either stranding the two poets high and dry or allowing Lowell to pace about like a lecturer wading into the shallows. Elsewhere, Lowell, in one of his manic phases, hitches a ride on a crescent moon through a door. And, in a tableau that seems quite eloquent about the poets’ respective reputations after death, Bishop, saying she would like to write from another planet, ascends on a mini-planetarium while Lowell gazes up at her from below. Such stunts could be said either to distract us unnecessarily from the main matter at hand or to provide some moments of visual stimulation in an otherwise static setting—the basic set is a stunningly accurate early Sixties-ish “brown study,” lit to give us times of day and projected upon to give us a sense of the outdoors that the oft-traveling duo travel through. Such effects mostly work and add interest, though that’s not to say one couldn’t easily imagine a stripped-down version of the play, without the Rep’s technical resources, dispensing with special effects and letting glowing prose provide all the color.

As Bishop, Fisher ages well into the part, from bright-eyed and young, she becomes bright-voiced and older. Her sense of Bishop’s steadiness never really flags, not even when the poet is getting a bit sloshed and an able stage-hand (Josiah Bania) has to come in to relieve her of her bottle, nor when she's forced to type one-handed due to an operation. We can intuit Bishop’s demons, but, in the letters used here, she mostly presents Lowell with a stoic outlook on her own travails and his, and crisp commentary on the same. And Lowell is recreated in a spot-on interpretation so close to the original it's magical: Mays wields the vaguely distracted air and the intense glare, the voice of bemused befuddlement delivering choice aperçus, and, of course, his Lowell is readier than Bishop to wear his Weltschmerz on his sleeve, but never—here anyway—becoming tedious about it.

Dear Elizabeth is a wonderful evocation of friendship, of the passion for the word that can unite lives that but rarely shared the same space—a few “interludes” presented in dumb-show capture the sometimes awkward, or worse, occasions when these two geniuses found themselves in each other’s presence. The play is wise and wistful, and delights with its slightly arch attitude toward persons who, in their rather single-minded pursuit of the art they shared in common, led messy lives they were never done commenting upon. Ruhl and Waters also let us consider that behind or beside the gimmicks of art, the rhetoric of poetry, and the feints of personality is, as Dickinson would say, “where the meanings are.”

Dear Elizabeth By Sarah Ruhl A play in letters from Elizabeth Bishop to Robert Lowell and back again Directed by Les Waters

A World Premiere

Scenic Designer: Adam Rigg; Costume Designer: Maria Hooper; Lighting Designer: Russell H. Campa; Sound Designer: Bray Poor; Projection Designer: Hannah Wasileski; Production Dramaturg: Amy Boratko; Casting Director: Tara Rubin Casting; Stage Manager: Kirstin Hodges; Original Music by Bray Poor and Jonathan Bell

Photographs by Joan Marcus, courtesy of The Yale Repertory Theatre

Yale Repertory Theatre November 30-December 22, 2012