Review of We Are Citizens, Theatre of the Oppressed New York, International Festival of Arts & Ideas

Linguist and political analyst Noam Chomsky once said that systems of justice “embody systems of … oppression, but they also embody a kind of groping towards the true humanely valuable concepts of justice and decency and love and kindness and sympathy”—values which, he added, “I think are real.”

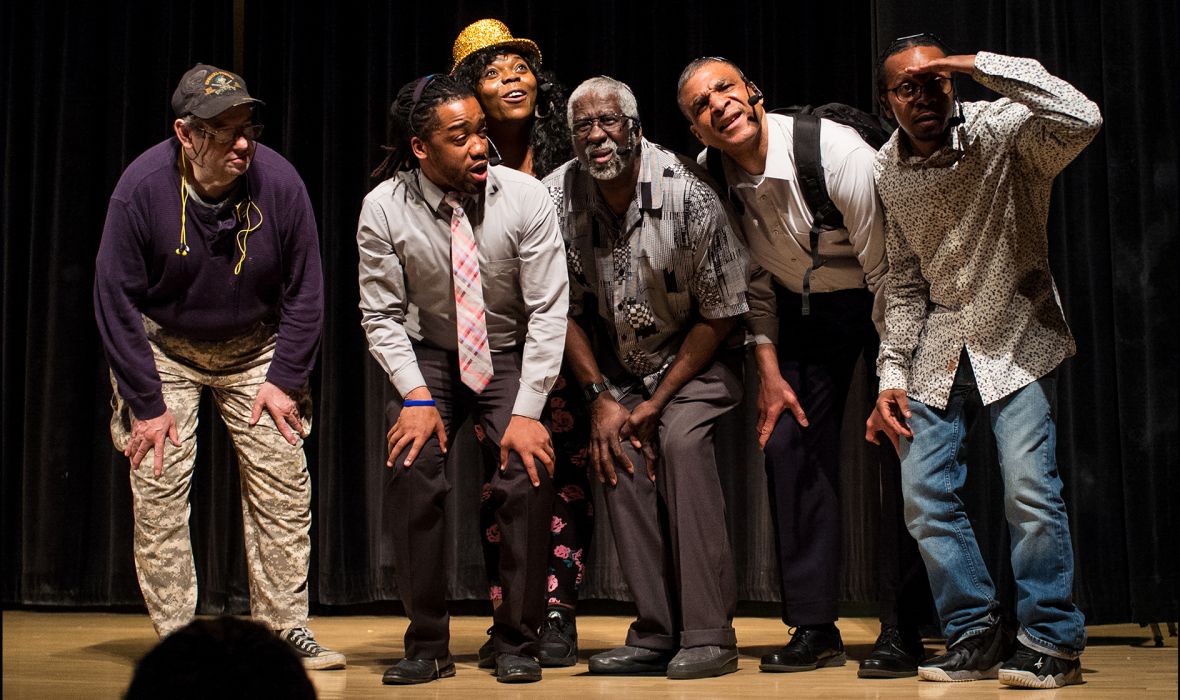

Theater of the Oppressed, New York, brings to performance spaces an effort to see how real such concepts or values are. With a residency in a location, the “Jokers” of TONYC work with volunteer residents to find a way to dramatize situations from their daily lives. The residents—or as the show at New Haven’s International Festival of Arts & Ideas insists, citizens—have faced some type of the oppression that Chomsky seems to have in mind. Generally, in the show I saw on June 21st at the Bregamos theater space in Erector Square, the oppression comes at the hands of institutions—medical, government agency, law enforcement—that are intended to help but can also harm, mainly by ignoring the humane elements of interaction that Chomsky names.

After an enactment of situations of friction, tension, and dysfunction caused by indifferent or incompetent professionals—acted out by non-actors with largely improvised dialogue—a segment called “Forum Theatre” is held. In that segment, it’s up to the audience—also citizens—to get involved and suggest ways to improve the situations presented. Then, to put money where their mouths are, so to speak, members of the audience are invited to try to enact their version of how things could or should go.

In the show I saw, not only were the Forum Theatre segments better at working with the problem than the original scenarios, they were also more lively and entertaining. The initial segment, set in an out-patient medical facility—a banner on stage read “Yale”—three patients who needed help with meds or with being admitted or with “hearing voices and seeing clowns” faced unhelpful staff and lots of double-talk, to say nothing of long wait times. The oppressed—already distressed by the condition that drove them to the facility in the first place—were in no condition to negotiate for what they needed. In the Forum Theatre segment, an audience member with a plan immediately pressed for a Patient Advocate and that brought at least some decency and dignity to the proceedings, even allowing the disgruntled patients to acknowledge the pressures under which the staff were working.

A problem between two women in a shelter—one using a blow-dryer to prepare for an important interview in the morning, the other trying to sleep—shouldn’t be that big a deal (haven’t we all had to deal with roommates?), but when an authority gets involved that can penalize one over the other, things can escalate. The audience member found a way to keep it between the women, overcoming the would-be sleeper’s excessive hostility.

Misgivings about giving a PIN number to a halfway house for ex-cons trying to make their way back into normal life are understandable. The staff member gave the uneasy man little concession and tried to make him the problem. The audience member invented a “cousin who’s a lawyer” to reach out to for advice—which may seem a special case—but the important point was that some king of shout-out was necessary, to find out if what was being asked was on the up-and-up.

The situations were not really life-threatening—except, perhaps, for the guy who felt he had to admit to suicidal tendencies just to be admitted and have his meds administered—but they did show how a little kindness and putting oneself into the other person’s position can go a long way in defusing potentially abusive situations where the antipathy isn’t personal, just routine. Putting oneself into the place of actors also makes for a kind of DIY theater experience that is unusual, not only showing—judging from audience response—how seeing a scenario enacted can make one think through a situation but also how acting things out makes the malleability of situations visible, as the role of oppressor or victim gets shifted around.

The main difficulty with amateur staging of situations for dramatic effect is projection. The average person doesn’t know how to speak to be heard by a roomful of people without shouting, so that the cries of “louder!” from the audience became more than a little distracting.

Theatre of the Oppressed NYC

We Are Citizens

John Leo, Liz Morgan, with: Vernette Bond, Kevin Creech, Robert (Bob Forlano), Alfred Gamble, Mark Griffin, Tammy Imre, Deborah Jackson, Joe Jackson, Diana Martinez, Mona Lisa Massallo, Robert Saunders, Shannon Smith, Betty Williams, Richard Youins (aka El Toro)

5:30 p.m. and 8 p.m., June 21, 2017

Bregamos Theater

* * * * *

Review of Never Stand Still, Onnie Chan, The International Festival of Arts & Ideas

Yale-China Association fellow Onnie Chan’s Never Stand Still, an immersive theater project based on a game, tries to keep its participants moving, and that’s all to the good, and it also seems to fracture any coherence to the event as best it can. Then again: if you’re playing a game you understand, then you have some idea why you’re playing, and what the stakes are. You generally have some idea of your opponent(s) and some idea of your own skill. When you go to see theater you’re not naturally in a competitive frame of mind and, as in this case, may have little idea of what the Game-Master is asking of you. The game gets confusing and stays that way.

Audience participants are divided into four groups—North, South, East, West—and they are in competition, supposedly, in a game called "Battlejong." The goal has something to do with triples and doubles, which has to do with Mahjong, and the methodology has something to do with Battleship (i.e., call out coordinates and get a “hit” or a “miss”). The particulars, it seems, are more of a distraction than anything, giving us activities as we gradually become aware that Jason, the figure behind all this who speaks and sings in voice-over, sometimes in Cantonese, is working through some issues, having to do with the death of his beloved grandma who was helping him keep it together. Jason may now be on a course of suicide or maybe even engaging in some kind of staged mass-event—like, for instance, creating a theater-game and making something awful or amazing happen to its participants. Or not.

The real world intrudes into the game as well. On the home-base for each group is an iPad on which one of four friends of Jason in Hong Kong is skyping live. They seem to function as touchstones for Jason, recalling moments from his past to help him stay focused. The friends don’t play much part in helping the teams, though I suppose they might if a team took the time to consult them.

Time for teams to do anything strategic seems to be a key thing to disrupt. So there is plenty to distract from the game we’re ostensibly playing. Like a SARS outbreak that will quarantine some of the audience. Like something having to do with air-guns (I missed this part because I was quarantined. I’m fine now.). And some kind of mounting drama about Jason’s precarious mental state.

In the end, which seemed to arrive abruptly and arbitrarily in the version I attended, you are free to choose one of three methods of egress: dead end, happy ending, or “something else.” I went for something else (of course). I won’t tell you what I learned but I will say you’re all a part of it. (I can’t fathom why someone would choose “dead end”—simply to negate a “happy ending?”) In any case, I heard from others what those choices led to, on June 22, but I don’t know if those are fixed or change.

In the playbill, Onnie Chan states that theater-goers don’t want simply to sit and watch a story performed; they want to be participants. Arguable, at best. In my experience with participatory theater, the quality of the event has often to do with the quality of the audience. This is partly true of all theater, but not to the same extent.

And there’s an interesting risk participatory theater runs: the audience members may seem more compelling than the theatrical event being staged and of which they are—tangentially—a part. You might find yourself wanting to duck out of any theater event, if you’re bored or distracted. But when the distraction is part of the event, then it’s possible you may become more interested in the group dynamics than in any assigned task or dramatic development.

Never Stand Still never quite managed to make either its staged drama or its participant activities clear and forceful enough to keep me in the game or the story. If that was the intention—to make one dissatisfied with entertainment—then it succeeded.

Never Stand Still (Immersive Game Theatre)

Directed and written by Onnie Chan

Producer: Steven Koernig; Set Designer: John Bondi; Lighting Designer: Jamie Burnett; Sound Designer: Kathy Ruvuna; Video Designer: William Wheeler; Graphic Designer: Dustin Tong; Stage Manager: Margaret Gleberman

Performers: Evan Gambardella, Xiaoqing Guo, King Wong, Lk Lo, Jenny Yip, Isabella Leung

The Iseman Theater

June 22-24, 2017