The farewell party for Cab 49, and its Artistic Directors Davina Moss, Kevin Hourigan, Ashley Chang, and Managing Director Steven Koernig, has been held; and the team for Cab 50 has been named: Artistic Directors Francesca Fernandez McKenzie, a rising third-year actor, and Josh Wilder, a rising third-year playwright, with Associate Artistic Director Rory Pelsue, a rising third-year director (and co-artistic director of this year’s Summer Cabaret), and Managing Director Rachel Shuey.

And now, before we start talking about the summer and next year, it’s time for the annual re-cap of the past season, in which I pick my favorites in a host of categories, saving my top choice for last. The idea of picking or naming a “best” is highly suspect, to me; but one can pick what one liked best, where the criteria may be as idiosyncratic as some of the work we’re talking about. And with that caveat, let’s go:

New plays: Works, in some cases never seen before, by YSD students that deserve recognition: Styx Songs, a collage of texts and original words all having to do with negotiating death, led by Jeremy O. Harris as a testy Hades; written by playwrights Majkin Holmquist and Tori Sampson; Xander Xyst, Dragon: 1, playwright Jeremy O. Harris’s merging of music, porn, Greek myths, and themes of sexual becoming; The Other World, dramaturg Charlie O’Malley’s tribute to the stylistic and soul-searching writings of artist and Aids activist David Wojnarowicz; Circling the Drain, costume designer Cole McCarty’s exploration of three women on the verge of confessional clarity, from short stories by Amanda Davis, and … Mrs. Galveston, playwright Sarah B. Mantell’s engaging and charming depiction of the delusions of age and the anxieties of youth and the bond of family.

Plays: Picking just five from this group is not easy, as the plays were many and varied; my choices are determined by what I found most provocative: Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again. Alice Birch’s absurdist, anarchic vignettes on the possibilities of gender solidarity; Caught, Christopher Chen’s sharp and clever commentary on the role of the artist in our culture and across cultures; The Slow Sound of Snow, Jabeer Ramezani and Payam Saeedi’s play, translated by Shadi Ghaheri, a beautiful, almost mythic treatment of life under conditions of compelling threat; In The Red and Brown Water, Tarell Alvin McCraney’s involving play of a woman coming of age, in tune with the ageless Orishas of the Yoruban religion, and … Débâcles, by Marion Aubert, translated by Erik Butler and Kimberly Jannarone, an almost slapstick farce of atrocity and brutality during the Nazi occupation of France, kind of like goosing history and giving it the finger at the same time.

Set: The ones I remember best are the ones that included some architectural marvel or unbelievable transformation of that little basement space: for Styx Songs, Ao Li built a graveyard fountain that wasn’t just for show; for In The Red and Brown Water, Annie Dauber constructed a cabin and porch with the cast flanking it; for The Quonsets, Sarah Nietfeld’s constructions created the sense of functional, intimate spaces in the great outdoors; for The Red Tent, Annie Dauber reimagined the Cab as a special space of decorative drapes and personal transformation; and … for Mrs. Galveston, Claire Marie DeLiso built a house as setting and expressive device and work of art.

Sound: Perhaps the most intangible part of production, so choices here tend to those that made sound stand out: In The Slow Sound of Snow (Tye Hunt Fitzgerald), every sound counted, and modulation between loud and soft was crucial; in Débâcles (Frederick Kennedy), the action was all over the place and couldn’t get lost in the spaces; in Xander Xyst, Dragon: 1 (Michael Costagliola), the contrast between miked song and intimate chat at tables and in bedrooms was striking; in Circling the Drain (Frederick Kennedy), the sound effects of horses and trains were subtle abettors of the tales; and … in Collisions (Christopher Ross-Ewart, Frederick Kennedy) the dazzling soundscape was a part of the whole, a mix of jazz music and speaking voice and song and other effects.

Lighting: A way of controlling our access to what is happening, lighting is most striking as a feature when it helps create the world of the play or adds special effects: In Collisions (Elizabeth Green, Krista Smith), lighting was an essential part of the whole effect of sound and sight; in In The Red and Brown Water (Carolina Ortiz), lighting was a subtle aid to our visualization of the different levels of the characters’ interactions; in Xander Xyst, Dragon: 1 (Erin Earle Fleming), there were different palettes of light for the different worlds—including virtual—of the action; in Circling the Drain (Krista Smith), the use of the spotlights made for dramatic and deliberate effects; and … in Styx Songs (Krista Smith) lighting was both mood and essential to story, an other-worldly presence.

Costumes: Help us understand characters but can also be delightful in their own right, here are some I especially liked: in Styx Songs, Sarah Woodham dressed Hades and a host of spirits with great panache; in The Slow Sound of Snow, Sophia Choi created a vocabulary of dress; in Thunder Above, Deeps Below, Cole McCarty’s color sense was eye-catching and dynamic; in Débâcles, Annie Dauber & Matthew Malone had a field day with a range of identifiable types, and … In the Red and Brown Water, Mika Eubanks kept it all plausible but also fictive.

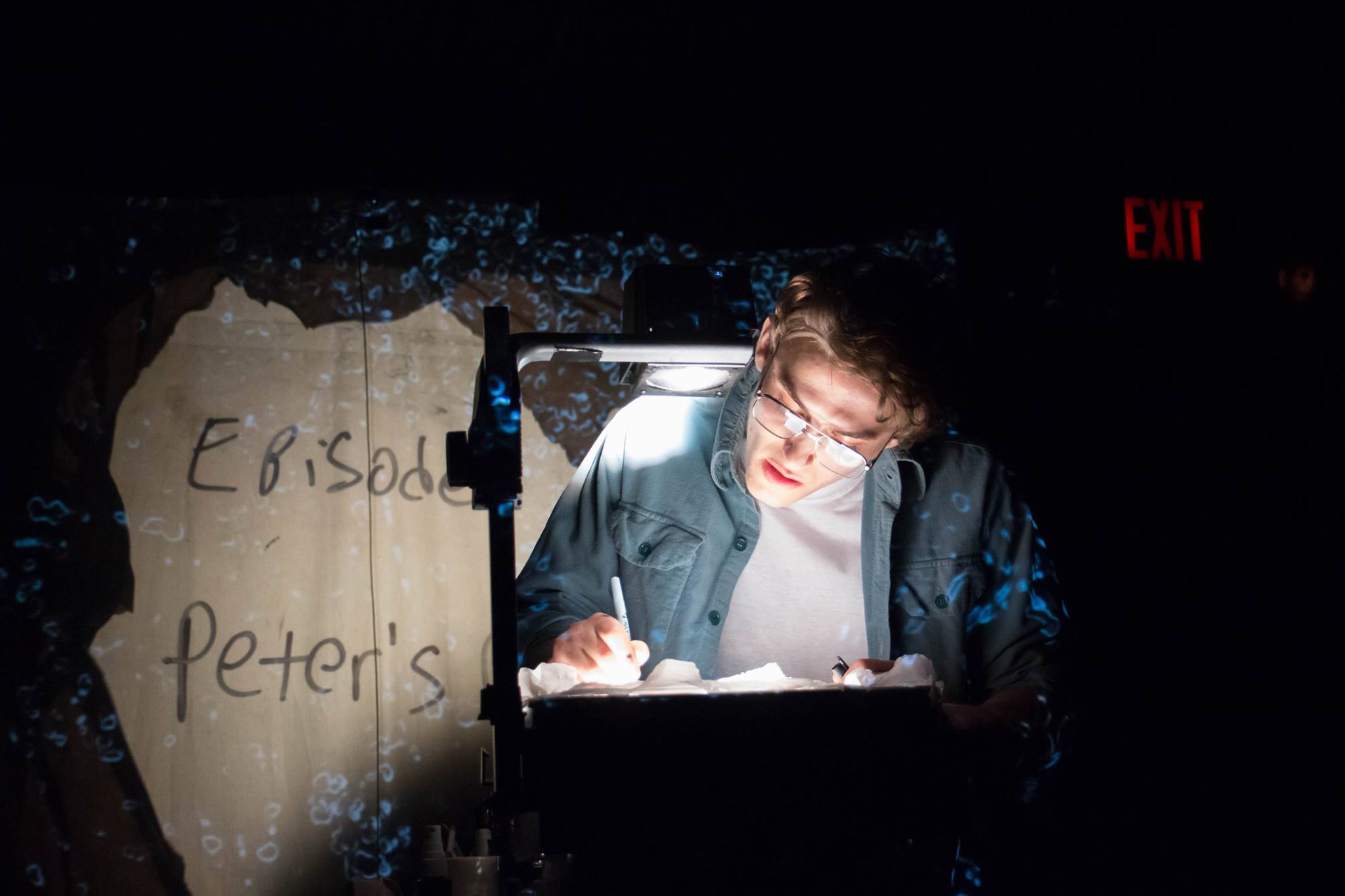

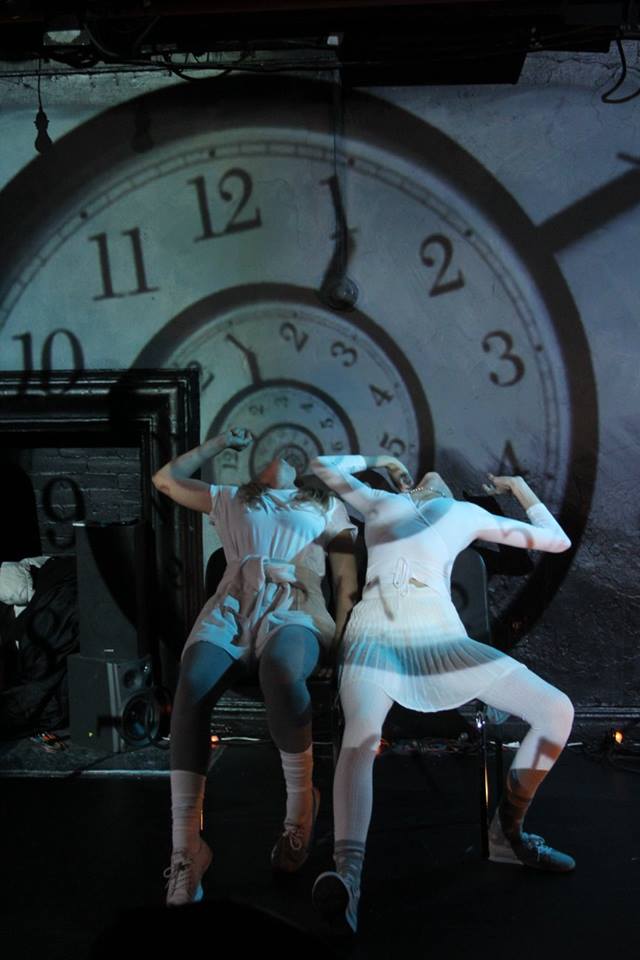

Projections: Not a key part of every production, but when present they can be much more than decorative: in Styx Songs, Erik Freer and Richard Green created an animation that was a major effect; in Collisions, Yana Birÿukova and Michael Commendatore made the action swim in projections to startling effect; in The Red Tent, Yaara Bar’s projections commented and provided context; in The Other World, Yana Birÿkova and Michael Commendatore shaped the background of the story; and … in Xander Xyst, Dragon: 1, Yaara Bar pulled out all the stops in making a virtual environment more fulfilling than the everyday.

Music: Not just an effect, music is intrinsic to some productions; here are some where its presence was a major part of the show: in Styx Songs, Sam Suggs’s compositions were essential to making this a show of songs; in Revolt. She Said. Revolt Again., Jiyeon Kim’s compositions provided subtle shifts in mood; in Xander Xyst, Dragon: 1, Isabella Summers, and Jeremy O. Harris with Stevan Cablayan created songs that reveal feeling and character; in The Red Tent, songs and dance music made a participatory texture; and … in Collisions, Frederick Kennedy and his musicians made involving, improvised music that interacted with visuals and action to create an event.

The next three categories deal with acting, the element of theater that, when all’s said and done, is still the most charismatic, helping to create “stars” and all kinds of audience identifications. Using the increasingly retrograde division according to the “gender” of the role, I’ve come up with five each, divided by the traditional binary. And, perhaps more importantly for Cab 49, five for “ensemble.” This year’s Cab was particularly strong in shows where “everyone” was in on the act, making for plays where the whole was more than the individual parts. Be that as it may, I’ve always got my eye out for the particular within the general.

Actors: James Udom as an anxious husband who might kill by procreating in The Slow Sound of Snow; Josh Goulding’s astounding one-man show as a foundling bedeviled by language in Kaspar; George Hampe’s comically beleaguered son and care-giver in Mrs. Galveston; José Espinosa as a maverick artist, at risk and on a quest in The Other World; and … Arturo Soria as a comical emotional contortionist and erring man-child in the world he never made of Débâcles.

Actresses: Moses Ingram as a young woman of spirit and skill facing a world of hurdles in In the Red and Brown Water; Danielle Chaves as a sister and daughter coming to grips with a painful past in North of Providence; Louisa Jacobson as an agent and confidante trying to be a friend in The Other World; Stephanie Machado as a young woman working through the affronts and assaults of a male-dominated world in Circling the Drain; and … Sydney Lemmon as an old woman alive with a compelling sense of what matters and what it means to get things right in Mrs. Galveston.

Ensemble: Ashley Chang, Anna Crivelli, Eston Fung, Elizabeth Harnett, Steven Lee Johnson bringing to life the slippery provocations of a situationist artist in Caught; Baize Buzan, Brontë England-Nelson, Sydney Lemmon, as acting instruments; Frederick Kennedy, Kevin Patton, Evan Smith, Matt Wigton, as musical instruments in the vibrant interactive environment of Collisions; Moses Ingram, Erron Crawford, Leland Fowler, Kineta Kunutu, Antoinette Crowe-Legacy, Amandla Jahava, Courtney Jamison, Jonathan Higginbotham, Kevin Hourigan, Jakeem Powell as a village’s worth of varied characters and archetypes in In the Red and Brown Water; José Espinosa, Rachel Kenney, Jake Lozano, Arturo Soria enacting the stringency of cannibalism as erotics, commodity, and ideology in The Meal; and … Antoinette Crowe-Legacy, Courtney Jamison, Stefani Kuo, James Udom, Seta Wainiqolo as unforgettable sufferers of existential dread, at war with and for their souls, in The Slow Sound of Snow.

Directors: In directing, I single-out the work that seemed to me to meet a challenge beyond the already considerable challenge of making compelling theater in a basement/restaurant: Lynda Paul for getting the tone of satire and seriousness with a varied cast, including non-actors, in Caught; Kevin Hourigan, with Frederick Kennedy for keeping the interplay of music and scene and speech so immediate and wonderful in Collisions; Tori Sampson for getting some of their best from everyone involved in In the Red and Brown Water, and for bringing a Folks production into the Cab; Elizabeth Dinkova for managing a wild ride of a play with more segments and themes than is conducive to mental health in Débâcles; and … Shadi Ghaheri for the incredible composure, pacing, and dramatic pay-offs of the haunting drama of The Slow Sound of Snow.

Production: They’re the shows that impress on many levels: technical realization, acting, directing, and, of course, what they express: Styx Songs, the season’s opener, an unforgettable dramatic experience that showed what the Cab is capable of (Producer: Trent Anderson; Dramaturg: Charlie O’Malley; Stage Manager: Sarah Thompson); The Slow Sound of Snow, profound theater that showed what the Cab can demand of its audience (Producer: Trent Anderson and Armando Huipe; Dramaturg: Ariel Sibert; Stage Manager: Michael Schermann); Collisions, an event, like a concert, but also more, as theater and multi-media exploration, different each night (Producer: Rachel Shuey; Dramaturgy: Ashley Chang, Jeremy O. Harris; Stage Manager: Paula R. Clarkson); Débâcles, a challenging comedy, a dark night of the collective soul delivered with incredible brio (Producer: Flo Low; Dramaturg: Gavin Whitehead; Stage Manager: Alexandra Cadena); and … In the Red and Brown Water, a bravura production, almost a Rep show in a basement, full of heart, a strong cast, and memorable dramatic features (Co-Producers: Lauren E. Banks, Al Heartley; Dramaturg: Lisa D. Richardson; Stage Manager: Olivia Plath)

Cab 49 has ended. All best to those who participated—many, week after week. For those who are graduating, go in peace. Everyone else: Get ready for Cab 50!

Yale Cabaret 49

Artistic Directors: Ashley Chang, Kevin Hourigan, Davina Moss

Managing Director: Steven Koernig

2016-17