Review of Mies Julie, Yale Summer Cabaret

August Strindberg’s nineteenth-century play Miss Julie is a gripping battle of the sexes situated as a class struggle as well. The possibilities of dominance by class—Miss Julie is the master’s daughter—come up against the social norm of male dominance—John is a very masculine groom who, by reason of his own knowledge of the world and of books, feels himself to be above his station. The play is a dynamic rendering of their struggle with their desires, their dissatisfaction with their roles, and their willingness to use, abuse, and maybe even—if it were possible—love one another. It has long been a staple of classic theater for its exploration of two people caught in an intense situation.

Yaël Farber has brilliantly adapted that situation to modern times, specifically South Africa on Freedom Day, almost a decade after apartheid’s end. The class division—Julie (Marié Botha) is still the master’s daughter grown up on a farm owned and run by her father, and John (James Udom) is still the master’s servant, who also grew up on the land—is now given further dimension by racial difference, and by the lingering, vexed question of reparations.

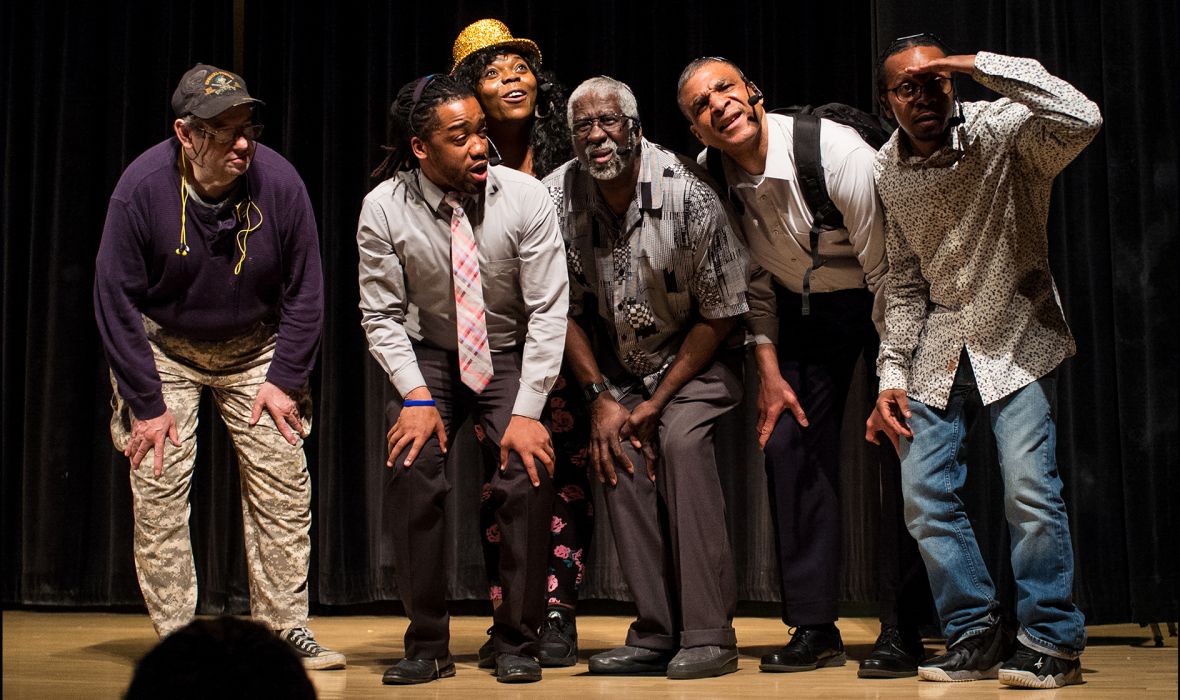

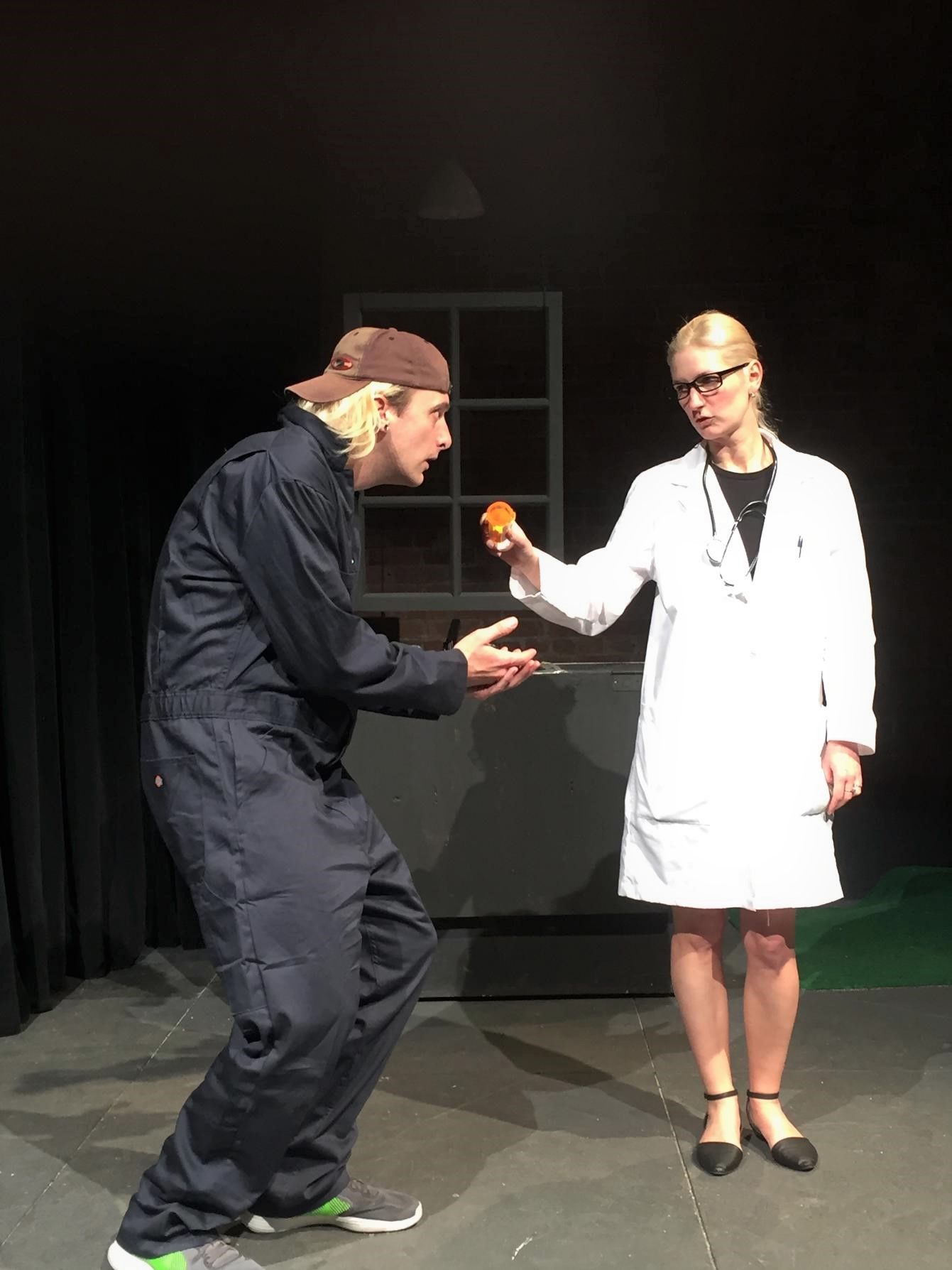

John (James Udom), Julie (Marie Botha) (photo: Yaara Bar)

The question of who actually owns the land the farm occupies is given a strong thematic element by the fact that John’s ancestors are buried beneath a tree whose roots are beneath the manor house’s kitchen, where all the action takes place. John’s mother, Christine (Kineta Kunutu) runs the kitchen and feels not only connected to the house she serves but also to the land where she wants to be buried with her forebears. As the play opens, John is clearly tired of his subservient role and believes the time is right to assert claims of independence and equality.

Julie becomes for John both a goad to overcoming any sense of social inferiority as well as a provocation to his manhood. And she plays to both urges, as well as exulting in the fact that he has had strong feelings for her ever since her mother—a distraught and neglectful woman who ultimately took her own life—brought the infant home. Julie sees Christine as a surrogate mother, so that the passion ignited between the boss’s daughter and the servant is further complicated by the fact that Christine, in essence, raised them both.

Ukhokho (Amandla Jahava), Christine (Kineta Kunutu) (photo: Yaara Bar)

A further dramatic element is the presence throughout the play of Ukhokho (Amandla Jahava), an ancestor spirit who acts as a kind of silent Greek chorus. Her interactions with the action take many subtle forms, and her mere visual presence is enough to make us feel how haunted the relations between John and Julie will swiftly become. The sense of past injustice is significant, but there is also something perhaps mythic in the land as well (and Sophia Choi's costumes and Fufan Zhang's set create a compelling overlap of eras). Farber deliberately evokes a sense of ties that extend well beyond a particular historical eventuality.

And, of course, the force of love and lust extend well beyond social forces. To see Julie and John come together is to see not only a celebration of the fact that interracial coupling is no longer an illegal immorality in South Africa, but a long-awaited release of tensions of attraction and resentment that have bedeviled both character’s lives. Director Rory Pelsue boldly lets sexuality play the part it must, and Botha and Udom bring off the scenes of coupling, so necessary to the physical dimension of their struggle, with great finesse.

Ukhokho (Amandla Jahava), Julie (Marie Botha) (photo: Yaara Bar)

The presence of Ukhokho—in Jahava’s very expressive and at times almost sprite-like incarnation—stacks the deck against Julie. Her blonde whiteness seems the anomaly it has always been, but even more so in this context. Botha’s Julie, while displaying some of the wild mood swings of the original, is more vulnerable than Miss Julie is generally considered to be, and she plays the part with an almost childlike wonder at the effect she is able to generate in her father’s smitten servant. Her efforts to humiliate him when he takes liberties have a charge that seems to chasten her in the same instant. And her insistence on the clarity of violence keeps a knife’s edge between them, but for one blissful moment.

As John, James Udom is fierce and strongly intelligent. He is able to convey John’s hopeless feelings as well as his sense of his own dignity. He won’t be Julie’s pawn, but he’s more concerned about being the pawn of his own passion and where that might lead. When his mother at one point slaps his face and cries “what have you done,” we feel the degree to which any act of his can destroy a delicate status quo, though John is never unaware. He simply chooses to ignore his mother and his duty when it suits him.

John (James Udom), Christine (Kineta Kunutu), Ukhokho (Amandla Jahava)

As Christine, Kunutu delivers her second very fine performance this summer at the Cabaret. In her own way, Christine is as fierce as her son, though in her case the power comes through as a “I shall not be moved” tenacity that no amount of importuning can weaken. Her “children” are playing with fire and out to destroy the status quo or themselves. Christine sees what there is to preserve—the land and the duty to the ancestors.

The force of the future colliding with the past shapes the choices these characters confront. In Strindberg, there’s nowhere the couple can go to live free of their past—such is the power of class relations that has poisoned their lives. In Farber’s contemporary world, the pair might go anywhere, almost, but what overrules them is the unfinished business of race relations in South Africa, a future that Farber’s play figures as a tide of blood.

Enthralling and fascinating and disturbing, the Yale Summer Cabaret’s Mies Julie adds more heat to a hot summer.

Julie (Marie Botha), John (James Udom) (photo: Yaara Bar)

Mies Julie

Retributions of Body & Soul

since the Bantu Land Act No. 27 of 1913

and the Immorality Act No. 5 of 1927

Written by Yaël Farber

Based on Miss Julie by August Strindberg

Directed by Rory Pelsue

Production Dramaturg: Charles O’Malley; Scenic Design: Fufan Zhang; Costume Design: Sophia Choi; Lighting Design: Elizabeth Green; Sound Design: Kathy Ruvuna; Stage Manager: Olivia Plath; Fight Choreographer: Emily Lutin

Cast: Marié Botha, Amandla Jahava, Kineta Kunutu, James Udom

Yale Summer Cabaret

July 14-23, 2017