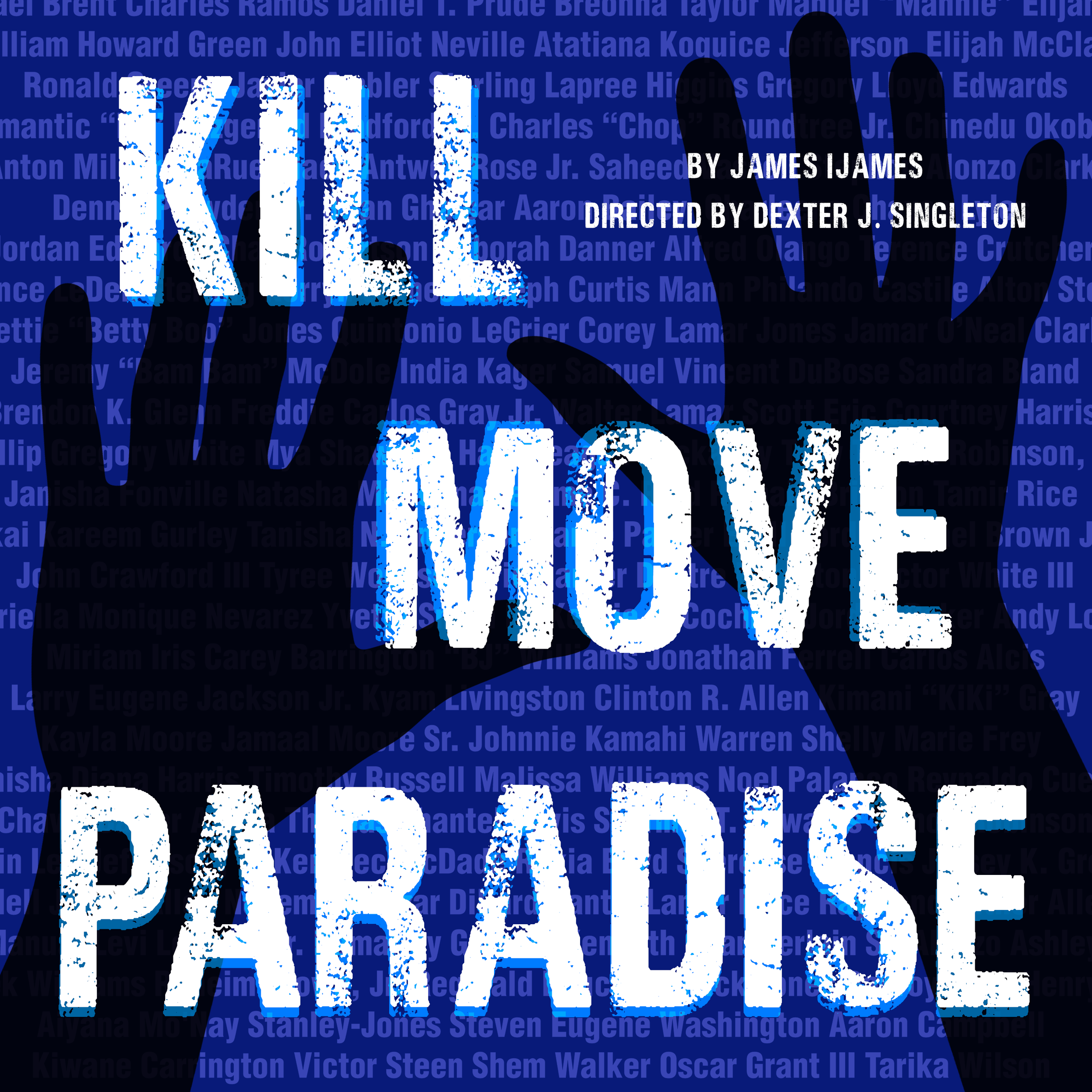

Review of KILL MOVE PARADISE, Playhouse on Park

The play for the Playhouse on Park debut of director Dexter J. Singleton, known in New Haven for his work as Founding Executive Artistic Director at Collective Consciousness Theatre, is well-chosen. At CCT, plays by authors of color are the norm, and dramas that confront issues of social justice even as they entertain and enlighten have been staged with great success. CCT is a black box theater which is why it’s quite a change to see Singleton’s work on an outdoors stage in Bushnell Park, Hartford. The open space and wide stage create an unusual atmosphere for what might otherwise be a somewhat claustrophobic play. James Ijames’ powerful KILL MOVE PARADISE is set in a fantasy afterlife, a “no exit” space seemingly reserved for black men who have died at the hands of police. The play ran live in person for three dates in late June and is available for streaming over the internet through August 1. Go here.

There’s something of a “Waiting for Godot” feel about the piece as the four characters, each arriving separately and at intervals, have to cope with determining their whereabouts and what is going on: Isa (Trevele Morgan), Grif (Oliver Sai Lester), Daz (Christopher Alexander Chukwueke), and Tiny (Quan Chambers), an adolescent. What’s more, this afterlife includes the audience. The idea of “fourth wall” doesn’t really apply as the space the men inhabit is not entirely clear even to them. The back wall is on a slant (a bit like a skateboard ramp) and occasionally one will try to climb it. At one point Daz goes behind it to retrieve a lawn chair. It’s the only prop in the play other than a printer that emits a constantly increasing list of the wrongfully slain.

The lawn chair is a fitting prop because the audience—visible in shots taken from its viewpoint—is sitting on lawn chairs. The outdoors aspect of the event makes for an interesting friction with the play’s mood. Even as the young men express their discomfort and anxiety, knowing that the “they” watching them is predominantly white (Isa calls it “America”), the audience seems relaxed and nonjudgmental. Admittedly, watching the play streamed on the computer adds a buffer for the viewer. One is able to feel that the audience there on the grass is the “they” the young men refer to, while “we” watch from some more remote location. That’s just one of those things about the presence and non-presence of online theater. Here, it adds a further implication since the “they” that has victimized these men and a host of other black U.S. citizens is always present but rarely acknowledged. It’s all of us, collectively, and none of us, individually as viewers. Determining how much one feels “called out” by what the men say about the audience is part of the play’s work.

The cast of James Ijames’ KILL MOVE PARADISE at Playhouse on Park, directed by Dexter J. Singleton (Photo by Meredith Longo)

The portions of the play in which the men struggle with this sense of how they should react to their situation are its most probing. Isa worries about profiling, Grif sees beauty in the crowd, Daz feels affronted by attitudes that tell him what he should be, and Tiny, the youth, finally confronts the crowd, fake pistol in hand, insisting “it’s not real. I’m real.” Such confrontational moments are almost haphazard, which is another way of saying that one never knows when they will arise.

The dramatic situation of being fatalities together but also still conscious and interacting makes for vivid give-and-take between the characters, though the tone tends to veer about a bit, making it hard to keep a read on who these four are, even to themselves. Add to that Ijames’ technique of keeping the play bouncing along by working in a pastiche format, including sitcoms, a soul-music song and dance, computer-game tagging, and a recital of stuff Daz noted backstage—some of it highly symbolic, some quite random, some a bit too heavily marked as racial baggage. We’re never in one reality for too long as if the sad fact of the four’s current status would be overwhelming, to us and to them, without some theatrical razzamatazz.

Isa (Trevele Morgan), foreground, Daz (Christopher Alexander Chukwueke) in James Ijames’ KILL MOVE PARADISE at Playhouse on Park (Photo by Meredith Longo)

Isa arrives first and is the most easily accommodating, both to his own situation and to dealing with the others. He’s practically a host, apt to read instructions aloud. Grif is more truculent and the one most likely to disrupt the easygoing mood Isa tries to maintain. Daz is the most “street” of the three, with a nickname “Dazzle,” and a “code name,” Daz, and a fondness for the phrase “my n---a.” His litany of what else is backstage where he found the chair seems oddly unfocused as if Daz refuses to endorse most of what he’s saying. At times, the three seem to accept each other, at other times they seem at odds even with the personalities they present.

At one point Isa reads out a list of black citizens who became fatal victims of police actions. The reading becomes a dramatic act of mourning and an overwhelming moment bordering on despair. Though that’s not the main mood of the piece, it’s important that it be registered, otherwise the theatrical aspects of the four’s situation could easily morph into a world where someone’s suffering is someone else’s entertainment.

Tiny (Quan Chambers), foreground, Grif (Oliver Sai Lester), Daz (Christopher Alexander Chukwueke), Isa (Trevele Morgan) in James Ijames’ KILL MOVE PARADISE at Playhouse on Park (photo by Meredith Longo)

The arrival of Tiny, still gripping the toy gun that occasioned his death, is an affront to the others as the most outrageous killing. The boy’s attitude makes for a nice contrast with theirs as he’s smart, sharp, and not easily intimidated. He inspires a certain compassion in the others if only because they enjoyed more life and experience than he did, and their effort to bring him along makes for a dramatic focus in the play’s second half. One could say that the point of the play’s action is for each of the four to understand his own death, to see it in the light of martyrdom or sacrifice or simply a bad break or a result of the systemic racism that each has had to deal with while denying its lethality, until now. An ironically charged moment in the play—acted as a sitcom complete with laugh-track—highlights the unreality of the characters’ situation, as if the enormity of Tiny’s death can only come home to him within a normative, albeit silly, frame.

The tonal shifts in the play can sometimes arrest its flow when it seems that it’s building to more extended considerations. It’s as if Ijames is worried that if he doesn’t keep things lively, he’ll lose our attention. The problem is that the dialogue is very elliptical and requires a lot of physical and verbal shifts, not all of which seem natural to the actors. Singleton makes the most of the wide stage, and the sound effects are very effective even in an outdoor setting The camera work and editing of the video version is excellent, making home-viewers feel they have the best seat in the house while also giving us a bit of a detached view.

In the end, KILL MOVE PARADISE is a nimble play that plays with our sense of dramatic conventions even as it makes us feel the force of its take on the dire situation of race relations in contemporary America.

KILL MOVE PARADISE

By James Ijames

Directed by Dexter J. Singleton

Cast: Quan Chambers, Christopher Alexander Chukwueke, Oliver Sai Lester, Trevele Morgan

Playhouse on Park

July 7-August 1, 2021