Review of Circling the Drain, Yale Cabaret

Amanda Davis’s stories, as portrayed in Circling the Drain, a new play by Cole McCarty adapted from Davis’s collection of the same name, feature female protagonists who suffer from bad relations with others. Three characters—Ellen (Rachel Kenney), Lily (Patricia Fa’asua), and Faith (Stephanie Machado)—bare their tales in an overlapping round-robin of increasingly harrowing misadventures. A fourth—The Fat Girl (Marié Botha)—inhabits Faith’s consciousness as an element of her past she still lives with. The deftly paced transitions in McCarty’s script create mini-cliffhanger effects as one woman or another holds the floor and then surrenders it to another speaker.

As interleaved monologues, the play works well, creating something of that circling sensation alluded to in the title. It also helps that the stories chosen have very different settings. Ellen’s takes place in Brooklyn, Lily’s out west, and Faith’s in a suburban high school. As with any drama where the characters confide to the audience, the feeling of immediacy is palpable, and all four actresses convey well the shifting sympathies of these characters’ commitment to their stories. It’s not that they are necessarily trying to convince us of something, but only want us to witness what they did or was done to them. In a sense, taking possession of the story is the whole point.

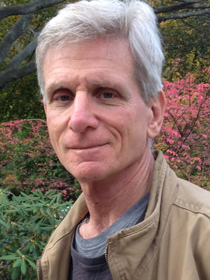

Ellen (Rachel Kenney), Faith (Stephanie Machado), Lily (Patricia Fa'asua)

Interestingly, the show, as the last in Cabaret 49’s season, takes us back to the beginning. Styx Songs, the first show of the season, featured an ensemble of characters sharing with us the means of their deaths, wanting to impress upon us what cost them their lives. Circling the Drain, less metaphysical, looks at the vulnerabilities that unite these women’s stories, costing them, if not their lives, then their peace of mind. The show’s subtitle “all that vacant possibility” would seem to suggest that, in each case, the story might have gone differently, that we aren’t dealing with fatalism, but rather with something more painfully contingent. And yet that’s not how the tales seem to play out. With no male characters or actors on view, there is no way to contrast an actual guy with the force of fascination, or fatal attraction, these women feel.

Ellen’s story is perhaps the most oblique, as presented. There’s a man in it—“not from around here”— and she eventually finds him in their bed with another guy. Her solution to the situation is to jump off a bridge. Because of how she presents it—in a rather poetic, fatalistic way—the situation feels fraught with peril but we don’t really get why that is. Kenney keeps us on Ellen’s side but the story of what happened to her, in her view, is a foregone conclusion as she tells it. There’s no other possibility because she seems never to entertain one.

With Lily’s story, a similar fatalism comes from the fact that she never doubts what she must do to make her object of desire—a cowboy with an almost symbiotic attachment to a horse—hers. This tale, in part because Fa’asua maintains an almost rapturous cadence in her telling, feels the most mythopoeic, as if there’s more to the story than simply a man and a woman, a blue shirt she knits him, and his beloved horse. The possibility here, if we accept it, might be in an exchange of symbols—the shirt for the horse, or the quest for a new horse to become the couple’s shared raison d’être. In any case, the story arrests us because, as with its descriptions of trains and plains, it has a strong symbolic beauty.

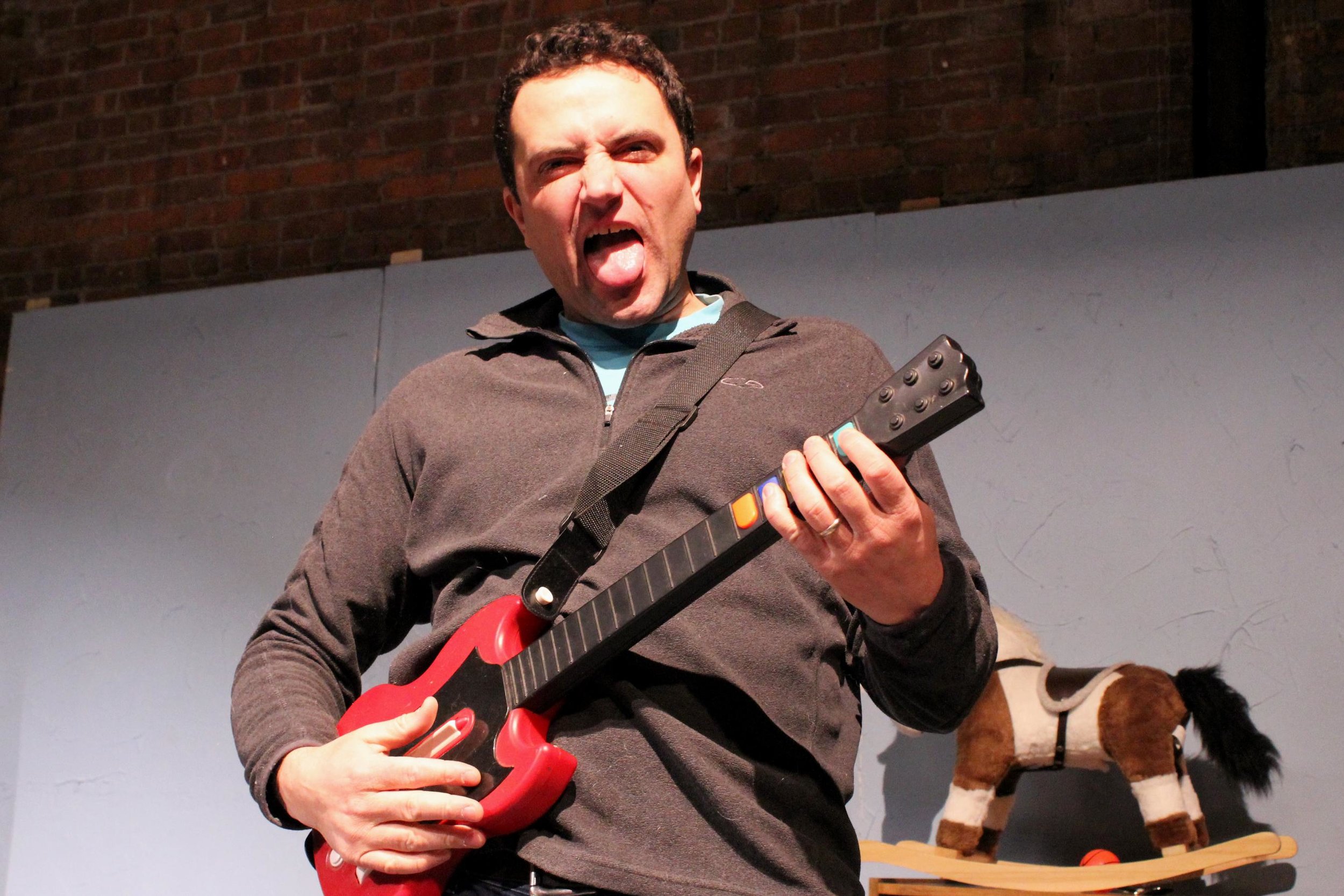

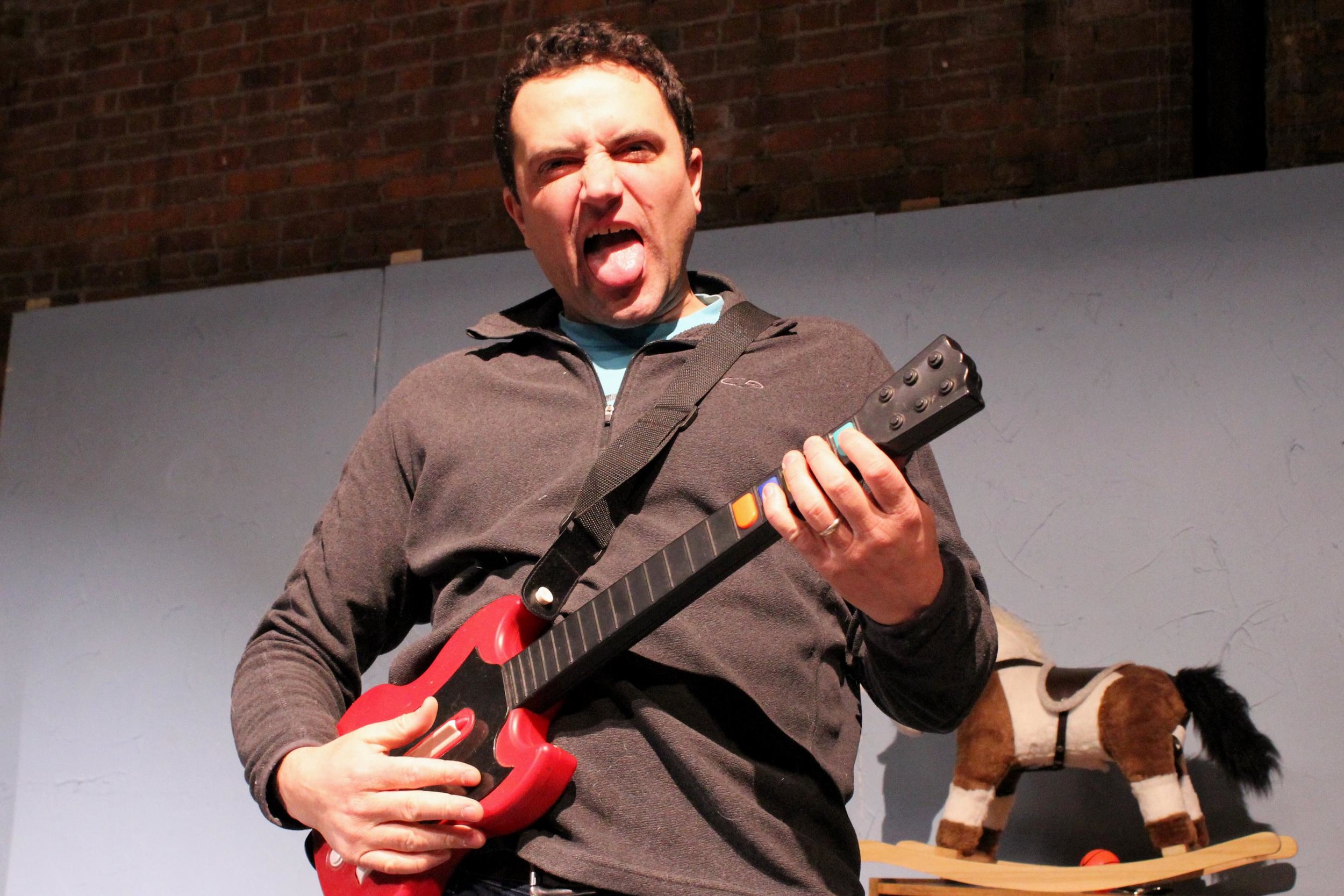

Faith’s story is the most graphically violent and the most realistic, if impressionistic. Its events illustrate the hazards of bullying, sexual predators, low self-esteem, and the desperate need to be loved that fuel many teen tragedies. Here, the interplay between Faith and the Fat Girl delivers some comedy, if in a somewhat caustic register, and that of course lulls us into a hope of Faith overcoming her demons. A brutal rape at the hands of a group of guys whose attention at first is gratifying makes Faith potentially the most damaged woman here, though her resilience is what might mystify us as much as Ellen’s fatalism and Lily’s symbolism.

All of which is a way of saying that these stories of women “circling the drain” probe for response, particularly when the characters are so alive before us. Machado, in particular, makes Faith—name noted—a woman who may prove to be more than her own story about herself. And that, we might say, is where the possibility lies: the power of not only articulating one’s story, but also overcoming it.

The set—a spare bleachers—and dramatic use of lighting and sound effects, for galloping horses and rushing subway trains, create a very malleable space, aided by simple touches like writing in chalk on the playing-space floor. Theater often provides a spectacle at which we stare, Circling the Drain takes us inside the heads of these women and leaves us there.

Circling the Drain or, all that vacant possibility

Directed & written by Cole McCarty

Adapted from stories by Amanda Davis

Dramaturg: Josh Goulding; Scenic Designer: Stephanie Cohen; Costume Designer: Beatrice Vena; Lighting Designer: Krista Smith; Sound Designer: Fred Kennedy; Stage Manager: Cate Worthington; Technical Director: Alix Reynolds; Producer: Lisa D. Richardson

Cast: Marié Botha, Patricia Fa’asua, Rachel Kenney, Stephanie Machado

Yale Cabaret

April 20-22, 2017